Mutual aid has become a buzzword among activists, community organizers, and academics in recent years. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, communities around the globe mobilized to meet the needs of their neighbors, and the term “mutual aid” took hold in the mainstream. Yet today in the post-lockdown world, there appear to be gaps in awareness of what the term means, where it came from, and what mutual aid actually looks like in practice. Although every organization is different, a large number of mutual aid groups offer assistance around food because food is an essential part of collective survival and wellbeing of the community. When existing systems fail to meet those essential needs in crisis, mutual aid delivers those needs to the community.

Dean Spade’s seminal work, Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During this Crisis (And the Next), defines mutual aid as “survival work,” done by ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances where government policies inadequately address crisis situations and even exacerbate structural inequities. When community care work is done in conjunction with ongoing social justice movements, this in Spade’s mind is mutual aid.1 Ride shares, free food and other survival items, community fundraising, prison letter-writing campaigns, and more can all fall under the umbrella of mutual aid. But more than this, mutual aid is about mobilizing communities to address a shared injustice and working together to collectively find solutions that don’t rely on any one person, corporation, or government entity.

The term mutual aid was coined by Russian anarchist philosopher Peter Kropotkin in a collection of anthropological essays published in the late 19th and early 20th centuries countering prevailing theories of social Darwinism. Kropotkin asks, who are the “fittest” in the theory of “survival of the fittest,” and postulates that in both the animal and human worlds, the most successful survivors are often the ones who mutually support their communities for the prosperity of the species as a whole.2

“What happens to one happens to us all. We can starve together or feast together. All flourishing is mutual…In our oldest stories, we are reminded that…when we rely deeply on other lives, there is an urgency to protect them.” -Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass

Humans have been participating in mutual aid long before it had a name. Indigenous and non-Western societies often prioritize collectivism and reciprocity over individual survival and continue to do so in the face of colonial oppression. The relief network Indigenous Mutual Aid writes “Indigenous Peoples have long-established practices of caring for each other for our survival, particularly in times of crisis. Mutual Aid is nothing new to Indigenous communities.”3 Diné organizers, Kauy Bahe, Radmilla Cody, and Brandon Benallie conceptualize their mutual aid work with the term k’é, the Navajo kinship system that asserts that the entire universe and everything in it is connected through a careful balance of reciprocity that must be intentionally maintained. During the COVID-19 outbreak their organization, K’é Infoshop, took relief efforts into their own hands rather than rely on the Navajo government, a once-horizontal leadership structure that shifted to a hierarchical model due to US trade pressures in the 1920s. Though they faced harassment from police and other officials, the Infoshop and associated local groups became essential distributors of food and medical supplies for their communities.4

The rich history of mutual aid in the so-called United States extends beyond Turtle Island’s original inhabitants. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, approximately one in three men were involved in fraternal organizations, such as the Freemasons and Rotary Club. These groups were wildly diverse, though many offered health care, medical “lodges,” and labor union support.5 Churches, of course, also have a long history of aiding their communities. For instance, in the wake of the Great Depression and World War Two, the Mennonite community across denominations in the US created Mennonite Mutual Aid (MMA) which offered legal and financial assistance for medical care and death and burial logistics.6

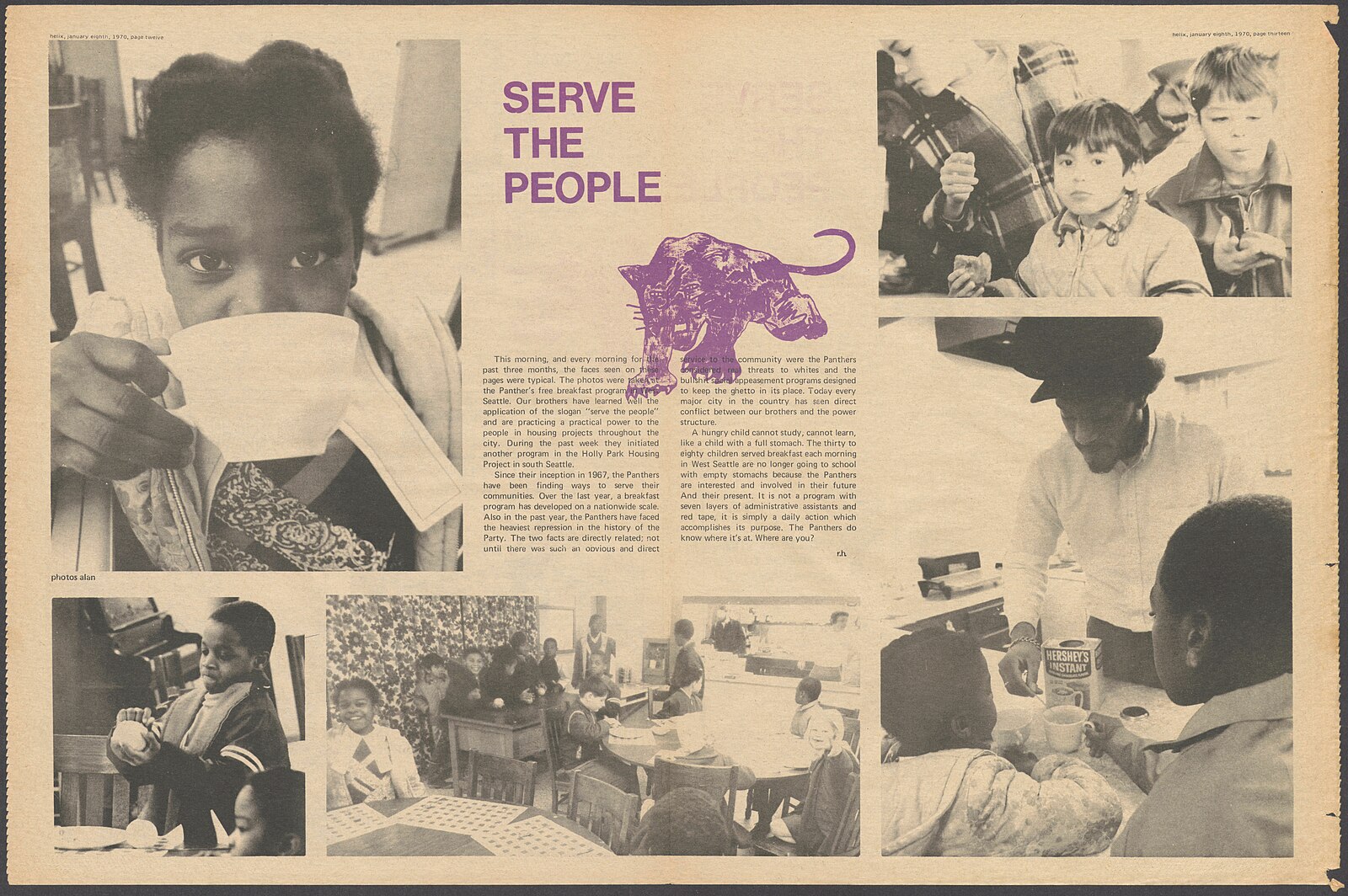

Probably the most famous example of mutual aid in recent history is the Black Panther Party’s (BPP) Breakfast for Children Program (BCP). The Party’s Survival Programs were considered just as essential and revolutionary as their other tactics, directly addressing issues of hunger, class oppression, and racism while increasing the community’s political consciousness and trust in the BPP. The first official Free Breakfast for School Children program began in January 1969 in Oakland, California. The premise was simple: children would do better in school if they had a nutritious breakfast before classes began. What started as an experiment at one local church blossomed into a nationwide initiative as communities took notice and came in droves, with some host sites serving over a thousand children each week.7

The FBI considered the Panthers to be a threat to national security and was particularly concerned with the public support that the Party garnered through the BCP. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover wrote in a 1969 memo to all field offices: “The BCP represents the best and most influential activity going for the BPP and, as such, is potentially the greatest threat to efforts by authorities to neutralize the BPP and destroy what it stands for”.8 Working closely with local police and through the Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO), the FBI sought to repress the BCP. Their tactics ranged from convincing parents that food was infected with “venereal disease” to sending riot-equipped police to interrupt children eating and destroy their food.9

A little more than a decade later, Food Not Bombs (FNB) was founded in Cambridge, MA in conjunction with the continuing anti-nuclear movement of the 1970s. Now a network of chapters that stretch around the globe, FNB continues to provide free food to all who come to their distributions. Founded in the midst of the anti-war and anti-violence movements, the food is always vegetarian or vegan, because as co-founder Keith McHenry writes, “society needs to promote life, not death.”10 Still FNB chapters, particularly those in the US, have faced harassment and arrest from law enforcement over the years. For example, in the summer of 2011, 28 FNB volunteers were arrested in Orlando alone for “illegally distributing food.11

Mutual aid groups often do work that traditional charities also perform, yet a Food Not Bombs chapter is much more likely to face police interference than a Salvation Army soup kitchen. Readers may wonder then why mutual aid organizations do not seek the same protections and legal recognition as a charitable organization would. For many mutual aid organizers, the very concept of “charity” is antithetical to mutual aid principles.

“Solidarity not charity” has become the unofficial rallying call of mutual aid organizers. While many mutual aid organizers find that charity encourages an “us vs. them” mentality, solidarity reflects a collective, systemic struggle as a rallying point for all involved in organizing. The collective struggle for the Black Panthers was white supremacy and racialized poverty. For Food Not Bombs, it was the anti-violence and anti-nuclear movement. Every mutual aid group will be different, but scholars like Oli Brown of Royal Holloway, University of London, and colleagues argue that a radical political framework is essential for true mutual aid organizing.12

Sean Parson, professor at Northern Arizona University, argues that the US’s nonprofit system as we know it today is the result of defunded welfare programs and increased reliance on corporate funding during the Reagan administration. This “neo-liberalization of social services” transformed charity into an industry where professionalism, maintaining tax-exempt status, and uplifting the needs of corporate donors and capitalist foundations fueled the work. Now, the nonprofit system encourages social movements to follow capitalist models, is monitored and influenced by state and corporate entities, and is generally focused on employing educated workers to the helping profession rather than mass activist organizing.11 Conversely, mutual aid organizers are attuned to the needs of the collective over any other stakeholder, and the lines between those offering and receiving assistance are blurred.

Mutual aid organizers acknowledge that the very concept of charity is steeped in the same structures of injustice that these groups strive to resist, largely white supremacy and capitalism. Indigenous Mutual Aid writes, “‘charity’ models of organizing and relief support…historically have treated our communities as ‘victims’ and only furthered dependency and stripped our autonomy from us.”3 Referring, among other things, to the destruction of indigenous foodways and forced dependency on government rations, Indigenous Mutual Aid asserts that the US government and present-day settler nonprofits do not appropriately seek to repair the harm done by colonialism, but instead feed into the concept of the “white savior.” Many contemporary charities have eligibility requirements for those receiving services based on sobriety, religious affiliation, income level, citizenship status, and more that arbitrarily assign deservingness to certain people and actively deny that food and shelter are essential human rights.

“The idea that those giving aid need to ‘fix’ people who are in need is based on the notion that people’s poverty and marginalization is not a systemic problem but is caused by their own personal shortcomings.” – Dean Spade, Mutual Aid

Because mutual aid encourages organizers to rethink and resist the way traditional social services operate, many mutual aid groups have difficulty designing leadership, decision-making, and funding models. Mutual aid groups are often most successful when lots of people come together and make decisions for the collective whole, but this is much easier said than done, especially when most of us are used to hierarchy and careerism. Dean Spade outlines some best practices for organizers, highlighting that the process is just as important a focus as the goal of helping people. Taking time to intentionally build processes that liberate the collective whole is a revolutionary act, even if it can feel boring!

Firstly, most mutual aid groups will follow a horizontal decision-making structure. This means that there are frequently no leaders, directors, CEOs, etc. Instead, all members of the group are involved in decision-making. Instead of relying on paychecks or urgency to move the work forward, well-structured mutual aid groups consider what intrinsically motivates volunteers to stay engaged. What makes someone want to keep showing up? Dean Spade argues that having a stake in the work and contributing to the decisions of the group makes participants feel a sense of co-ownership that prevents burnout and turnover.1 He recommends consensus decision-making which allows for everyone to have a say in any decisions that affect them. For instance, while a traditional food pantry might have a set list of the types of foods that can and cannot be given away, a mutual aid group will make decisions as a collective on which foods are distributed, prioritizing the needs of those receiving food just as much if not more than those serving the food. In our interview with Washington Square Park Mutual Aid, we learned that their most popular food item, pizza, is a weekly staple at the request of the community that loves having “Friday Pizza Parties.”

Financially supporting the work of a mutual aid group can also look very different from traditional charitable organizations, often relying primarily on grassroots crowdfunding. Some groups, like Food Not Bombs, specifically warn against seeking tax-exempt status.10 Gaining nonprofit status, acquiring funding, and hiring paid staff does not necessarily mean that an organization is not a mutual aid group, though Dean Spade cautions that this financial access can make it more difficult for an organization to stay true to their mission. Inequity can arise when some members are paid and some are volunteers. Paid members may suddenly be expected to do more for the group than unpaid counterparts and decision-making may start to skew to favor the opinions of paid members. Additionally, the skills necessary to understand the legal and clerical caveats that come with managing grant funding may make these paid positions available only to more privileged members. This is antithetical to a key principle of mutual aid which asserts that anyone and everyone has a valuable role to play, regardless of their professional and educational background. Finally, grant funding often comes with certain restrictions and stipulations by funders on how the money may be used as well as which political issues the organization is able to publicly address.1 That said, some groups, like East Brooklyn Mutual Aid, have found success in acquiring tax-exempt status and locating funding sources that allow the group to operate in line with their existing goals and values.

While books like Dean Spade’s Mutual Aid are useful guides to understanding how a mutual aid group functions, every organization is different, as every community will have different needs, values, and priorities. The community itself is the most important component of mutual aid, as is empowering said community to have agency in their collective survival and wellbeing. Many mutual aid groups work around food because food is an essential part of collective survival and wellbeing of the community. Mutual aid is about mobilizing communities to address a shared injustice and working together to collectively find solutions.

The CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute interviewed two mutual aid groups in NYC that began during the COVID-19 pandemic and continue to feed their communities today: Washington Square Park Mutual Aid (WSPMA) and East Brooklyn Mutual Aid (EBMA). Both are doing fantastic work for New Yorkers, and we encourage you to read both interviews and learn more about how to get involved! WSPMA is a grassroots group with a horizontal leadership structure and anarchist values. In contrast, EBMA is a 501(c)(3) with big goals to transform the food landscape in East Brooklyn. We also encourage you to research mutual aid organizations in your community and learn by volunteering! If you live in New York City, you can use this helpful database to find a group near you.

Finally, if you’d like to learn more, please take a look at our suggested readings on mutual aid.

Sources

- Spade, D. (2020). Mutual aid: Building Solidarity during this crisis (and the next). Verso.

- Kropotkin, P., & Bonzo, N. O. (2021). Mutual aid: An illuminated factor of evolution. PM Press.

- Indigenous Mutual Aid, & Indigenous Action. (2020). Zine: How to start an indigenous mutual aid covid-19 relief project. Indigenous Mutual Aid. https://www.indigenousmutualaid.org/mutual-aid-101-organizing-guide/

- Nowell, C. (2020, September 26). In the Navajo Nation, anarchism has indigenous roots. The Nation. https://www.thenation.com/article/activism/anarchism-navajo-aid/

- Adereth, M. (2020, June 14). The United States has a long history of mutual aid organizing. Jacobin. https://jacobin.com/2020/06/mutual-aid-united-states-unions

- Nolt. (1998). Formal Mutual Aid Structures among American Mennonites and Brethren: Assimilation and Reconstructed Ethnicity. Journal of American Ethnic History, 17(3), 71–86.

- Potorti. (2017). “Feeding the Revolution”: the Black Panther Party, Hunger, and Community Survival. Journal of African American Studies (New Brunswick, N.J.), 21(1), 85–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12111-017-9345-9

- Pope, R.J., Flanigan, S.T. Revolution for Breakfast: Intersections of Activism, Service, and Violence in the Black Panther Party’s Community Service Programs. Soc Just Res 26, 445–470 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-013-0197-8

- Churchill, W. (2014).To disrupt, discredit, and destroy: the FBI’s secret war against the Black Panther Party. In K. Cleaver & G. Katsiaficas (Eds.), Liberation, imagination, and the Black Panther Party: a new look at the Black Panthers and their legacy (pp.78–117). New York: Routledge.

- McHenry, Keith. 2012. Hungry For Peace: how you can help end poverty and war with Food Not Bombs. Tuscon: See Sharp Press.

- Parson, S. (2014). Breaking bread, sharing soup, and smashing the state: Food not bombs and anarchist critiques of the neoliberal charity state. Theory in Action, 7(4), 33-51. doi:https://doi.org/10.3798/tia.1937-0237.14026

- Mould, O., Cole, J., Badger, A. & Brown, P. (2022) Solidarity, not charity: Learning the lessons of the COVID-19 pandemic to reconceptualise the radicality of mutual aid. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 47, 866–879. Available from: https://doi-org.ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1111/tran.12553

Suggested Readings

Books:

- Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During This Crisis (And the Next) – Dean Spade

- Hungry For Peace: How you can help end poverty and war with Food Not Bombs – Keith McHenry

- Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice – Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

Articles and Zines:

- Migrant community responses to the COVID-19 pandemic: Mutual aid at La Morada – Alexandra Délano Alonso and Daria Samway

- Solidarity, not charity: Learning the lessons of the COVID-19 pandemic to reconceptualise the radicality of mutual aid – Oli Mould, Jennifer Cole, Adam Badger, and Philip Brown

- How to start an Indigenous Mutual Aid COVID-19 Relief Project