Introduction

School meals provided under the USDA’s National School Lunch Program (NSLP) and School Breakfast Program contribute substantially to students’ daily dietary intake. Children from low-income households, who rely on school meals as a significant source of nutrition and calories1 benefit the most, making school food a program that helps to close gaps in access to healthy food. COVID-19 related school closures beginning in March 2020 were followed by reports of doubling levels of food insecurity in households with children, a situation widely attributed to the loss of school meals.2,3 In the period between March 2, 2020 and May 2, 2020, children missed more than 72 million school meals in New York State alone.3

In response, Federal policy makers enacted Pandemic EBT (P-EBT) through the Families First Coronavirus Response Act of 2020, the first response of Congress to the hardships imposed by the pandemic. P-EBT is a federal program that authorizes states to distribute money to families to help cover the cost of replacing free meals their children would have received in school under NSLP if not for school closures due to COVID-19.4,5

Initial Impact

A national evaluation of the program found that P-EBT reduced food hardship by 30% in the week following its disbursement among children in the lowest income category. The program has lifted an estimated 2.7 to 3.9 million out of hunger.6

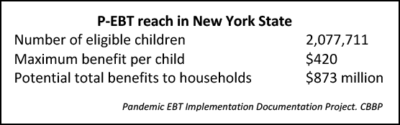

Further, a study of a pilot program for school aged children, which utilized eligibility and implementation approaches similar to P-EBT and disbursed food benefits on EBT cards to replace student meals missed during out of school time was found to significantly decrease food insecurity in the summer, a time when many children lose the nutritional benefit of school meals.7 In New York State, as shown above, P-EBT had the potential to add up to $873 million to the incomes of families with children enrolled in k-12 schools, increasing their food purchasing power and supporting local food businesses.

Phase I: P-EBT Implementation in New York State During the 2019-2020 Academic Year

P-EBT implementation varied by State, and the federal government required all states to cover half of the administrative costs for the program during the 2019-2020 school year.4 New York reported the third largest pool of eligible children and potential benefits disbursed, with more than 2 million children eligible.8 New York State’s implementation plan was approved on May 6, 2020 and distribution of benefits spanned from May – September 2020.

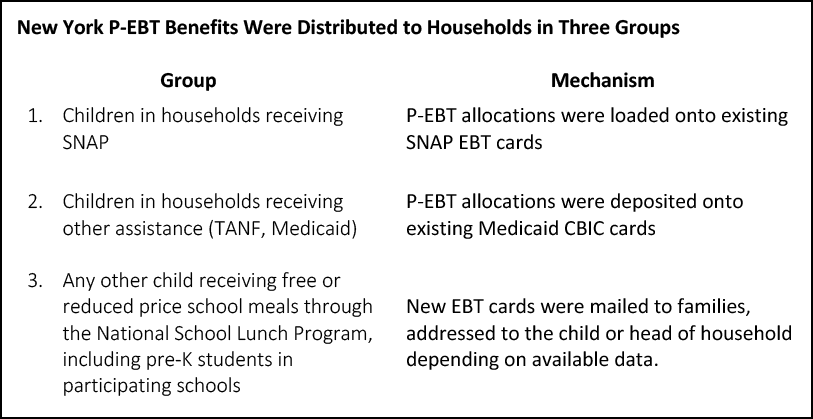

New York issued P-EBT benefits directly to households (direct issuance), while other states required an application or a mix of direct issuance and application procedures.

Implementation required deep collaboration and data sharing between Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance (OTDA), New York’s State Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) agency, and the New York State Education Department (NYSED) and authorized school authorities which administer and implement the NSLP. The agencies invested significant effort towards establishing data sharing agreements for matching student school enrollment from a centralized student data system and benefit data.8 OTDA employed over 175 full time equivalent staff for implementation of the program.9

Through partnership with advocacy groups and community-based service providers, the agencies distributed outreach and communication on the program in multiple languages. Eligible households received letters, and were targeted with webinars, social media, digital ads, and direct text and email messages from school districts.9 Potential users could make inquiries about the program through an OTDA-run call center and email inbox.8

Good Practice in New York

A comprehensive report on the national implementation of P-EBT by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), a national policy research organization, identified several highly effective practices for carrying out the program.8 Among these practices that New York State implemented in Phase I are:

- CBPP identified the direct issuance model implemented in New York as the “most effective” and “least burdensome system for families and states.”

- New York state provided the most generous reimbursement possible and implemented a distribution approach aimed at maximizing reach to as many children as possible.10

- Assignment of P-EBT cards in the child’s name (rather than Head of Household) meant that necessary information for disbursement could be found in existing data sources, thus streamlining the process and eliminating the need for eligible families to take action to receive benefits. Assignment to the child’s name also helped to alleviate concerns of undocumented immigrants wanting to ensure their children could access food benefits despite uncertainty over public charge rules.

- New York mailed letters to SNAP households to alert them of additional P-EBT benefits being added to their cards, and quickly distributed P-EBT benefits to SNAP households.10

- New York implemented a customer service infrastructure including a hotline and informative website to provide essential information to households.10

Obstacles in New York

Though direct issuance eliminated the need for eligible households to apply for P-EBT, the reliance on school districts for student data combined with school staff across the state working remotely (often disconnected from secure school servers) challenged schools to collect and organize these data expeditiously. Schools struggled, too, in providing accurate addresses for all households, since this information had not been collected since the start of the 2019-2020 school year. Time required to complete this process caused significant delays in disbursement, as well as uncertainty and lack of clarity in communication to households about when they could expect to receive benefits. In addition to data-related delays, the state tasked only a limited number of EBT card vendors with meeting the unprecedented demand for card provision. In New York, Conduent Incorporated, a national company that provides technology services to governments and businesses, issues New York state P-EBT cards. The company recently reported a 26% increase in EBT card distribution across 24 states since April 2020—and revenues of more than $1 billion in the third quarter, due primarily to its pandemic related services.11 However, some households did not receive benefits until September 2020 – more than 5 months after school closures began and children started to miss meals.

Community based providers and hunger advocates reported confusion and frustration on behalf of households who struggled to receive and activate their benefits. Many users reported that the need to activate their benefits was itself a barrier, as many households in the second and third distribution groups struggled to “pin” and activate their benefits cards due to differing PIN requirements. Some households in Group 2 reported that they did not have Common Benefit Identification Cards (CBIC) cards so did not have a way to spend their benefits.10 As of December 2020, approximately 96,000 homes of children whose P-EBT food benefits were issued on CBIC cards had not yet redeemed any P-EBT benefits.12

Despite the efforts of community groups to provide critical information and one on one technical support to users, the reliance on OTDA for accurate content and guidance created challenges and delays in communication that stoked clients’ dissatisfaction. Further, OTDA’s direct customer service infrastructure initially struggled to meet the demand of households requesting support, and clients reported long telephone hotline wait times.13 In some cases, troubleshooting put the burden of determining eligibility based on NSLP participation on the child’s family, requiring them to reach out to their child’s school to inquire about why they might be missing from the master eligibility list provided to OTDA.10 Anecdotal reports suggest customer service staff occasionally provided inconsistent information, leading to increased confusion and frustration among clients.10

Phase II: Academic Year 2020-2021 and Beyond

In the face of the continuing COVID-19 pandemic and ongoing realities of school closures and persistent food insecurity, Congress extended P-EBT for the 2020-2021 school year. As of mid-January 2021, OTDA still awaits approval from the USDA in order to issue P-EBT benefits to eligible students for the 2020-2021 school year. New York families with eligible children have been advised that they should not expect to receive P-EBT for the 2020-2021 school year until March 2021 at the earliest.14

Recommendations

Recommendations for implementation over the next six months

While awaiting approval from USDA for Phase II implementation, OTDA should:

- Issue retroactive benefits to households missed during Round 1 of implementation. OTDA could seek to close open cases of missed benefits from the first phase of disbursement to ensure that all Phase I eligible children are compensated for meals missed during the Spring of 2020.10 As high levels of child food insecurity persist, such a decision would bring additional resources for food to insecure children and families.

- Continue to clean and refine the master eligibility list and solicit missing information from households who believe they are newly eligible for the program. Using this time to prepare and improve data quality and the interoperability of data systems will position OTDA well for execution and timely disbursement of benefits once USDA provides guidance. Broad solicitation (for example, via text message) of households to provide updated address and eligibility data to OTDA can decrease the number of cards mailed to wrong addresses or returned.4 The creation of an online portal or hotline through which parents can check and confirm their household address on file could also support an improved master eligibility list. Moreover, an automated system would not require much staffing, making it an efficient way to reach and enroll eligible clients.

- Maximize communications and outreach around the P-EBT program. Communication about P-EBT should include information specific to various user groups such as immigrant households and non-SNAP users about where and how to use benefits. For example, OTDA should provide additional information for immigrant families fearful of using their benefits due to concern about public charge rules. For non-SNAP users, information about which farmers markets and alternative food retailers accept SNAP would be useful to consumers unfamiliar with EBT. P-EBT communication and outreach should also provide information on how to apply for other benefit programs such as Unemployment Insurance, SNAP, WIC, and Medicaid. Maximizing communication opportunities can support increased use of benefits and expand the reach of the program.

- Simplify the process for new P-EBT card activation by updating SNAP call scripts and allocating resources to P-EBT specific communication phone lines, email inboxes, and online forms for inquiry. In Phase I, OTDA relied too heavily on established SNAP communication systems. Though similar to SNAP, activation processes for P-EBT differed enough to lead to confusion and frustration for many clients using the SNAP call lines to troubleshoot. Establishing specific P-EBT systems and P-EBT specific scripts will help to alleviate this issue and streamline client service and enrollment.

Recommendations for Federal Policy

- Develop federal guidance for P-EBT continuation that anticipates and accounts for the unpredictable and rapid changes in school remote learning schedules and closures within districts. As much as possible, USDA should enable States and school districts to apply robust simplifying assumptions about missed school meals and a range of childcare settings to maximize the P-EBT reimbursement provided to households. This might involve collaborations among various state agencies including Office of Children and Family Services (OCFS), Department of Health (DOH), and the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP).10

- Make P-EBT disbursements for the 2020-2021 school year regular and frequent. New York’s first phase of P-EBT disbursement happened at a single point in time, with many households receiving benefits months later than they experienced missed school meals. Phase II disbursements should be distributed monthly, on a one-month lag to allow for accounting based on school closures and simplifying assumptions. Distributing benefits on a standard schedule, as with SNAP, will allow households to plan for and include P-EBT in their food budget and purchase essential items accordingly.

Recommendations for New York City and State Policy

- Create a specific New York State mechanism for notifying and enrolling newly eligible families. New York was one of only 13 states that did not include newly eligible households in P-EBT provision. Community Eligibility across New York City school districts meant that any household with children enrolled in public school (approximately 1,126,501 students)15 received P-EBT benefit in Phase I, a condition that allowed the program to serve many newly food insecure families as the pandemic progressed in Spring 2020. However, more than 45% of the State’s eligible Phase I households live outside of New York City, and newly eligible households in these communities have not yet been enrolled in the program. Other states have been successful in enrolling newly eligible households in real time and these efforts provide a number of viable models for implementation in New York, including: automatic P-EBT enrollment for households with children who apply and qualify for SNAP, enrollment by application of households who apply and qualify for free/reduced NSLP. Enrolling newly eligible families in New York State would support increased access of benefits and expand the reach of the program. This mechanism could also be useful for ensuring that eligible households who were missed in Phase I disbursement have a process for resolving their case.

- Issue new P-EBT cards rather than rely on CBIC cards to better serve eligible households receiving Medicaid (but not SNAP). This change could simplify communications about pinning to ensure that Group 2 households are able to access their benefits while minimizing undue administrative burden.10

- Increase participation of New York City and State officials, particularly Mayor Bill de Blasio and Governor Andrew Cuomo, in mass communication efforts about the P-EBT program. During the pandemic, New York State’s Governor and New York City’s Mayor have played an important role in promoting pandemic relief programs and educating residents about the pandemic and the responses. However, neither official has spoken regularly about P-EBT, a missed opportunity to make more New Yorkers aware of this important program to reduce food insecurity in NYC. Communication about the program largely fell on advocacy and community serving organizations. These organizations did an impressive job in spreading the word about obtaining P-EBT benefits, but they lack the public platform and voice of prominent New York officials. Given early evidence of the impact of the program in reducing food insecurity, in Phase II elected New York City and State officials, including representatives in the City Council and state legislature, should speak more regularly about P-EBT, including details on how households can access and use their benefits. Broad public communication at this level can support increased access of benefits and expand the reach of the program.

- Invest in more advanced monitoring and evaluation of P-EBT implementation. In New York’s initial P-EBT implementation plan, OTDA agreed to submit monthly reports to USDA detailing a limited number of program outputs, including: a) number of children receiving P-EBT; b) number of households receiving P-EBT; c) total dollar value of P-EBT issued; d) Average P-EBT issuance amount per household.16 In Phase II, New York should re-allocate funding previously required for program implementation (with the Federal government paying all overhead costs in Phase II) to track these and other metrics that could improve program accountability, and inform efforts to increase access. Examples could include data on the number of newly issued cards returned or activated, by zip code; number of newly eligible households who apply and are granted benefits, by zip code; rate of reach of eligible children, by zip code. Other functions that warrant assessment are the efficacy of communications (e.g., response time inquiries to troubleshooting) and the impact of the program (e.g., self-reported measures of food security of representative samples of users and utilization of other food benefit and emergency food programs).

- Take responsibility for conducting direct outreach to eligible households and educating them about the program. In instances where CBOs and EFPs are called upon to liaise with households, New York City should allocate funding to compensate these organizations for their P-EBT communication and support efforts. In Phase I, the City relied on the partnership of mission driven organizations throughout the state to distribute essential information about P-EBT. In Phase II, in addition to enhanced direct outreach, the City should provide selected partners with financial support to achieve specific outreach and communication goals in order to both maximize P-EBT communication opportunities and bolster mission driven organizations experiencing increased COVID-19 related demands.

Conclusion

The first phase of P-EBT implementation in New York represents a number of advances. In Phase I, New York made EBT benefits eligible to a wide cross section of the population, including those typically excluded from regular SNAP programs. By including all families with children in school in NYC, whatever their income or documentation status, P-EBT extends the logic of the “Free School Meals for All” movement and its beliefs that universal access to healthy food is both a human right and a strategy to reduce stigma. A key challenge for Phase II is to sustain this level of availability and to document that it contributes to a statewide reduction in food insecurity rates.

Another key accomplishment is that P-EBT extends from school buildings to grocery stores the foundational belief behind school food programs – that society benefits when students receive essential nutrition to support their academic progress. Food retail markets such as grocery stores and bodegas are a more accessible and convenient source of healthy affordable food than emergency food providers (food pantries and soup kitchens). Further, use of P-EBT at retail markets has the added benefit of injecting money into local economies. Can this extension set a precedent for other ways to blend the two largest federal food support programs – SNAP and school food – beyond the COVID-19 pandemic?

Finally, P-EBT in New York demonstrated that well-intentioned and seemingly straightforward program design (direct issuance) can be undermined by inadequate attention to logistics, and the nuts and bolts of enrollment. Future iterations of the program in New York and all states should engage end-users in designing enrollment procedures and pilot testing. Further, though OTDA’s efforts to implement such a comprehensive effort warrant praise, more direct (and financially supported) engagement of community-based organizations may be able to reach eligible families faster and with fewer logistical challenges.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the WT Grant Foundation and Spencer Foundation for their support of this work.

About the CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute

The CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute is an academic research and action center at the CUNY Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy located in Harlem, NYC. The Institute provides evidence to inform municipal policies that promote equitable access to healthy, affordable food.

About Hunger Free America

Hunger Free America is a nonpartisan, national nonprofit organization building the movement to enact the policies and programs needed to end domestic hunger and ensure that all Americans have sufficient access to nutritious food.

Suggested citation

Fraser KT, Pereira J, Poppendieck J, Tavarez E, Berg J, and Freudenberg N. Pandemic EBT in New York State: Lessons from the 2019-2020 Academic Year and Recommendations for 2020-2021 and Beyond. CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute and Hunger Free America, 2021.

References

1. Cullen KW, Chen T-A. The contribution of the USDA school breakfast and lunch program meals to student daily dietary intake. Prev Med Rep. 2016;5:82–85.

2. Bitler MP, Hoynes HW, and Schanzenbach DW. The social safety net in the wake of COVID-19. Brookings. 2020.

3. Kinsey EW, Hecht AA, et al. School Closures During COVID-19: Opportunities for Innovation in Meal Service. AJPH. November 2020. 110:11: 1635.

4. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2020, October). Lessons From Early Implementation of Pandemic-EBT Opportunities to Strengthen Rollout for School Year 2020-2021.

5. Frequently Asked Questions for the Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer (P-EBT) Food Benefits.

6. Bauer L, Pitts A, Ruffini K, and Whitmore Schanzenbach D. The Effect of Pandemic EBT on Measures of Food Hardship. The Hamilton Project. July 2020. Brookings.

7. Collins AM, Briefel R, Klerman JA, et al. Summer Electronic Benefit Transfer for Children (SEBTC) demonstration: summary report 2011–2014.

8. Pandemic EBT Implementation Documentation Project. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. September 2020.

9. Documenting P-EBT Implementation in New York. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

10. Notes from Hunger Solutions Agenda for Debrief/Suggestions for NYS Extension of P-EBT. November 16, 2020.

11. Conduent Assists Millions of U.S. Residents through Pandemic EBT and Other Government Support Programs. GlobeNewswire. Conduent Business Services. August 3, 2020.

12. WBNG. Did you receive this text? Your Pandemic-EBT benefits may still be available. December 1, 2020.

13. Notes from Food Access Benefits Call, hosted by Hunger Free America. August 2020.

14. SNAP COVID-19 Information. Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance. New York State. Accessed: January 12, 2021.

15. NYC Department of Education. DOE Data at a Glance. Accessed: November 9, 2020.

16. Pandemic Electronic Benefits Transfer Program (P-EBT) Approval of New York State Plan. USDA Food and Nutrition Service. May 6, 2020.