Introduction

Hunger and food insecurity have long been recognized as persistent problems in the US. In the last year, the COVID-19 epidemic and its economic consequences have pushed millions of additional children and young people in the U.S. into food insecurity, jeopardizing their current and future well-being and health. Recent research suggests that as many as 50.4 million Americans (15.6%) were food insecure in 2020, with 17 million of them children (23.1% of the U.S. child population).1 Strong evidence documents the long term adverse physical health, mental health, educational and social consequences of food insecurity in the first 2 decades of life.2,3,4 Thus, new federal, state, and city resources allocated to reducing food insecurity resulting from the COVID-19 epidemic and its economic consequences provide an opportunity for the United States to test innovative approaches to making progress towards the vital but elusive goal of creating and enacting the public policies necessary to end food insecurity and hunger among U.S. children.

Since 2000, local, state, and national governments in the United States have worked in tandem to modify federally-funded public food programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Special Supplemental Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and Child Nutrition Programs in response to human, natural and economic disruptions, including in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. These officials have changed eligibility criteria, increased funding for benefits, expanded outreach and education, facilitated enrollment and re-certification, and applied new technologies such as Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) and online enrollment for SNAP and WIC. Although a robust body of evidence on these initiatives exists, it has not been systematically summarized and assessed for relevance to the current pandemic, nor organized to be useful for policymakers and advocates.

The CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute, in partnership with Hunger Free America, conducted a scoping review to integrate and synthesize established evidence-based practices with “practice-based evidence”5 on the varying circumstances of past emergencies that have threatened food security and the food policies and programs implemented in response. Scoping reviews address broad research questions aimed at mapping key concepts and the extent of evidence in a defined area. This study takes a broad and exploratory scope and maps key concepts and gaps in evidence related to this particular niche of food policy. By systematically searching, selecting, and synthesizing data from academic and gray literature, public policy reports, and media accounts of implementation and impact, among others, this study aims to advance food policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic by presenting a rigorous policy-relevant analysis of the evidence of the effects of various approaches to expanding public benefits in response to emergencies that threatened to increase food insecurity and hunger during the period 2000 to 2020.

Scoping Review Methods And Results

We conducted a scoping review to:

- Identify and summarize available evidence on the efforts of to modify food benefit programs in response to emergencies over the last 20 years;

- Describe the ways in which food benefit programs interact, work in tandem and add maximum value to support vulnerable populations during crises;

- Identify key facilitators and barriers to effective implementation and impact of these programs;

- Assess the relevance of this evidence to addressing food insecurity triggered by the current COVID-19 pandemic.

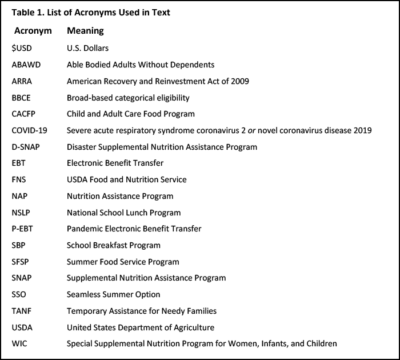

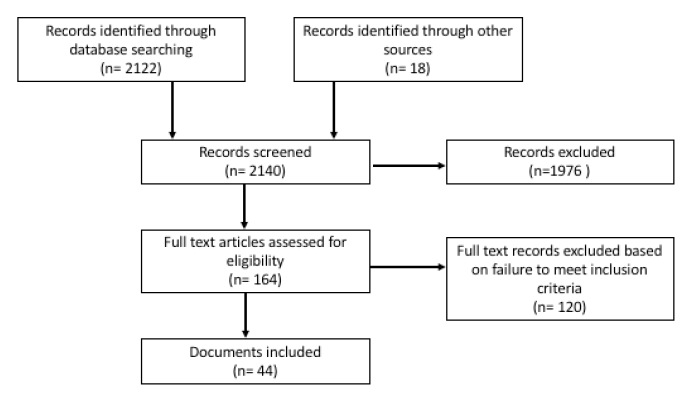

A number of academic and public information sources were identified in consultation with the CUNY Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy Librarian, and systematically searched using a defined set of electronic search terms. More than 2140 documents were identified and screened according to a comprehensive set of inclusion and exclusion criteria. After review, 44 documents were included for analysis (Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Flow diagram for the scoping review process adapted from PRISMA-ScR guidelines.6

Of those documents included in this analysis, more than half (n=23) referred to modifications to SNAP and nearly as many (n=21) referred to disaster specific implementation of the Disaster Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (D-SNAP) and USDA Commodity Food Disaster Distribution programs. A smaller number of sources referred to modifications to Child Nutrition Programs such as National School Lunch Program (NSLP), School Breakfast Program (SBP), and Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) (n=7) and WIC (n=5.) Documents referring to other programs such as nutrition incentive efforts (i.e., Double Up Food Bucks) and other relief programs such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and Nutrition Assistance Program (NAP) for U.S. Territories were mentioned infrequently. Notably, only 18% (n=8) of the documents reviewed reported program or policy impact data.

Additionally, review of State by State FNS Disaster Assistance Data from October 2016-December 20207 assessed 96 state/territory specific food policy responses to 72 distinct “disaster” events. An in-depth analysis of specific food policy response revealed 53 distinct packages of food policy modifications used in response to crises documented by FNS. The most utilized modifications to food programs were quantified, with the most often implemented being:

- SNAP waivers for timely reporting for replacement of lost food due to disaster;

- SNAP automatic replacement of benefits for individuals in disaster affected areas;

- D-SNAP implementation;

- Child Nutrition Programs waivers of meal pattern requirements for NSLP/SBP, SSO, SFSP;

- SNAP waivers to enable purchase of hot food with EBT benefits.

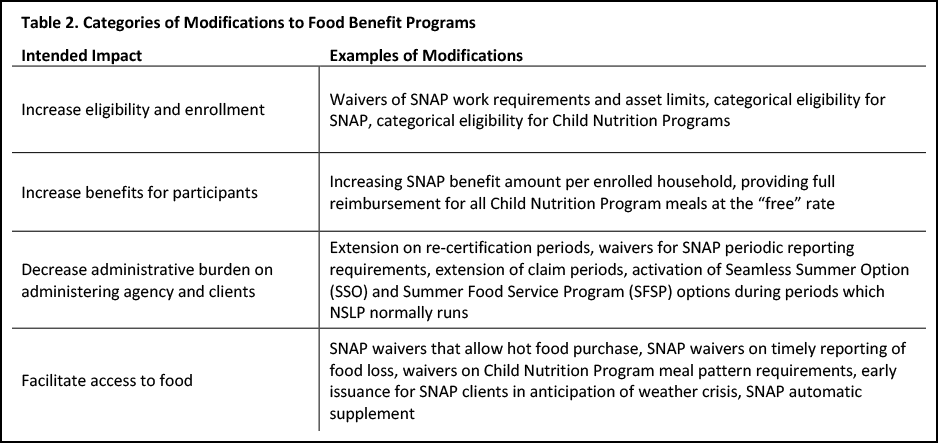

Based on comprehensive analysis of all resources included in this scoping review, we categorize food benefit programs in response to crises into distinct groups based on intended impact of these modifications in Table 2.

Key Findings

Impact of Food Program Modifications in Response to Crises

From the impact data available on food policy response to past crises, a few key lessons are discernable:

- High levels of engagement in food benefit programs among eligible populations during periods of non-crisis can be protective during periods of active crisis and its aftermath. A study found that high levels of SNAP participation among eligible Oregon residents prior to the 2008 Recession meant that SNAP participants had longer periods of participation and a reduced likelihood of losing benefits due to administrative issues during and after the Recession compared to states (i.e. Florida) which had low levels of pre-Recession program participation.8

- Increasing maximum SNAP benefit to households can increase program participation, increase household resource for food purchases, and decrease food insecurity among very low-income households. Recession era modifications increased the maximum SNAP benefit for households by 13.6%, which further increased incentive to enroll in the program, resulting in a 3% increase in program participation by low income households. SNAP benefits received by the typical (median) participating household increased by 16%, thus increasing household resource for food purchases by 5.4%9 resulting in reductions in food insecurity.10 Food insecurity was expected to rise in 2008-2009 as a result of the Recession, but instead it fell during that period among very low food secure households by 2%, a result largely attributed to the benefit increase and increased enrollment in the program.9,10

- Broad-Based Categorical Eligibility (BBCE) for SNAP at the state level can increase the pool of eligible households and promote program enrollment during economic downturn. BBCE is a policy in which households may become categorically eligible for SNAP because they qualify for a non-cash Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) or state maintenance of effort (MOE) funded benefit. USDA encouraged state adoption of BBCE for SNAP enrollment during the Great Recession and by 2011 37 states had adopted it, leading to increased SNAP eligibility and enrollment by 1.0 million individuals.10,11

- SNAP waivers for Able Bodied Adults Without Dependents (ABAWD) are an effective mechanism for increasing program enrollment by expanding the eligible pool of applicants and providing a greater incentive for households to apply. SNAP waivers on time limits for work requirements for ABAWD during the Great Recession expanded the eligible pool of SNAP applicants and provided a greater incentive for people to apply for a longer duration of receiving benefits. It is estimated that this waiver increased SNAP enrollment by 1.9 million individuals.11

- Policy modifications such as the SNAP Expanded Disaster Evacuee Policy and flexibilities to the Child Nutrition Program that enable multiple school districts to operate out of the same location but claim meals separately are effective mechanisms for serving misplaced individuals immediately after a crisis. These modifications adeptly address immediate need for food and help to lower administrative burden for clients during times of crisis.12,13,14

Facilitators to Effective Implementation of Food Policy Response to Crises

Large scale, multi-state, complex emergencies that threaten to increase food insecurity and hunger require a multi-pronged food policy response that both enhances the utility and reach of standing safety net programs while also activating additional emergency specific programs to meet short- and long-term food needs. These multi-pronged food policy responses seem to have the greatest impact when they address food insecurity as well as economic stimulus and recovery. SNAP, for example, creates an economic stimulus of $1.50 for every $1.00 of food benefits spent during a weak economy.15 Since food access and long-term food security are inextricably linked to housing and income, food policy responses that also promote economic stimulus are particularly salient.9

Table 1 categorizes modifications according to their intended impact. Our review of past food policy response indicates that a multi-pronged approach that pulls from various categories of modification may be important for promoting the effectiveness of the total response. We note that the response to less widespread crises tends to rely on a single type of modifications to a single program (i.e., SNAP waivers for timely reporting of individual requests for replacement of lost food due to disaster), but that modifications that increase benefit amounts or decrease administrative burden are used in tandem less frequently. Based on evidence of impact from large crises such as Hurricane Katrina and the Great Recession, we encourage policymakers to consider more multi-pronged response utilizing numerous categories of response type to increase the effectiveness of overall food policy response.

Challenges in Implementing Food Policy Response to Crises

Detailed account of the challenges to implementing food policy in response to crises is also limited to documentation of a handful of well-recognized major events such as the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, the Great Recession, and Hurricane Katrina. Challenges encountered in implementing food policy response during these crises lend themselves to several lessons applicable for future response:

- Administrative costs should be covered in full by federal support to maximize state level implementation and program effectiveness. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 included nearly $300 million over two years to support states in meeting administrative demands related to increased caseloads of food benefit programs. Even so, several states were required to cut back on staff (rather than scale up to meet demand) due to budget constraints.16 Similarly, state level response to Hurricane Katrina was hobbled by the standard SNAP requirement that states cover 50% of administrative costs.17 Both instances illustrate how limited administrative budget restrictions can hinder program impact.

- Effective food policy responses require policy makers to assert directly the priority of food related outcomes. Reports documenting the September 11 policy response largely describe measures to addressing housing and job displacement, and a key challenge cited for September 11 food policy response is the multi-pronged nature of the September 11 disaster; food insecurity was an issue, but policy makers did not make reducing it an explicit priority.18

- State level implementation of federal food policy response to multi-state crisis mean that households impacted to the same degree in different states might receive different levels of support. As such, equity issues were raised following analysis of multi-state response to Hurricane Katrina. As many as 15 years later, the model for state level implementation persists, with little to no conversation had regarding how to ensure equitable response across state lines.17

Limitations of Available Evidence

Of the documents captured for this scoping review, few sources report evaluation findings or report on the overall impact of efforts to modify food programs in response to emergencies. Literature documenting impact of food policy response to major crises appears to be limited to two major events of the last 20 years: The Great Recession and Hurricane Katrina. The paucity of impact data is problematic on multiple levels. First, a lack of impact data means that policy makers looking to learn from prior implementations of policy response must rely on output data on program reach and $USD benefits distribution (which our review notes is also limited) to determine whether program modifications were effective. While it is helpful to understand how many people were served by a given policy response, and the dollar amount of benefits distributed, these metrics do not convey the impact of these benefits on individual food security and hunger in the short or long term. Nor do they offer a framework for understanding how individuals would have fared if given policies had not been implemented. Second, a lack of impact data ultimately leaves legislators with less decision-making power, forcing them to rely on previous patterns of policy implementation to inform future policy response. But doing things a certain way because that is the way they have always been done, rather than learning from past successes and failures, optimizes neither program effectiveness nor efficiency.

Recommendations For the COVID-19 Era And Beyond

- Invest financial and human capital to strengthen the evaluation of emergency food policy response, with a focus on outcomes such as food security, diet quality, and economic stimulus.

- Combine policies from multiple categories of intended impact (i.e., increase eligibility and enrollment, increase benefits for participants, decrease administrative burden on administering agency and clients, and facilitate access to food) to strengthen outcomes of emergency response.

- Cover administrative costs fully with federal support in order to maximize state level implementation of food policies and program effectiveness.

- Increase the maximum SNAP benefit for all households and maintain this increase well beyond the resolution of the crisis.

- Make equitable distribution of benefits across states a priority through federal guidance for state implementation.

Conclusion

This scoping review demonstrates that few studies document the impact of crisis-driven food benefit modifications on food insecurity and hunger, the key outcomes of interest. A greater number of documents present output level details about the economic spending ($USD) and reach (total number of individuals served) by modified food benefit programs, and a large number of documents more simply describe food policy response to specific crises without providing evaluation of that response. Our analysis points to SNAP and Child Nutrition Programs as the most modified food benefit programs in the wake of U.S. crises. The review concludes with several considerations for continued food policy response to the ongoing COVID-19 crisis.

Our findings from this scoping review can inform responses to the current COVID-19 pandemic and the economic upheaval it has triggered, events which threaten food security for tens of millions of Americans, especially children and young people. USDA FNS has responded to the COVID-19 pandemic with extensive modifications and waivers to SNAP, Child Nutrition Programs, WIC, and USDA Commodity Foods Distribution programs. While some child focused waivers, such as P-EBT and expansion of SNAP online purchasing to support social distancing, are new, many others show the same flexibility observed in response to previous crises of the last 20 years.

Among the past food policy response to crises reviewed here, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, launched in response to the Great Recession, may be the most applicable to the present pandemic. Notable lessons from the food policy response to the Great Recession suggest further steps the federal government can take to minimize the pandemic’s impact on national rates of food insecurity and hunger. Among these, the absorption of food benefit program full administrative costs to facilitate state agency implementation is paramount. Further, as states have a high level of decision-making power in flexibilities for food benefit programs, federal guidance to states should emphasize and encourage approaches that maximize equity for vulnerable populations at risk for hunger and food insecurity residing in different states.

As the pandemic persists, it will be critical to monitor its ongoing impact on hunger and food insecurity across the nation even as the public health crisis is resolved and the economy begins to recover. Past crises show that food insecurity can endure, especially for populations at higher risk. The policy flexibility applied to food benefit programs during COVID-19 highlight the bureaucratic complexities of making decisions about the operation of safety net programs. Rules on work requirements, asset limits, and other means tests can either extend or limit the actual impact of these programs, leaving vulnerable populations covered or excluded. The growing crisis in food insecurity exacerbates long standing inequities and highlights persistent problems in the nation’s food system. The pandemic and its dire economic consequences and the widespread public, policy makers and civil society responses to rising food insecurity and hunger suggest that COVID-19 has the potential to increase support for permanent repairs to the nation’s social safety net programs and thus achieve a higher standard of food security for all Americans.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the WT Grant Foundation and Spencer Foundation for their support of this work.

The following individuals, listed in alphabetical order, helped prepare this report: Morgan Ames, Joel Berg, Nevin Cohen, Katherine Tomaino Fraser, Nicholas Freudenberg, Yvette Ng, Emily Pagano, Ivonne Quiroz, Kit Sathong, Sarah Shapiro, Emma Lingshan Sun, Emilio Tavarez, and Craig Willingham.

About the CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute

The CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute is an academic research and action center at the CUNY Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy located in Harlem, NYC. The Institute provides evidence to inform municipal policies that promote equitable access to healthy, affordable food.

About Hunger Free America

Hunger Free America is a nonpartisan, national nonprofit organization building the movement to enact the policies and programs needed to end domestic hunger and ensure that all Americans have sufficient access to nutritious food.

Suggested citation

Lessons for the COVID-19 Era From 20 Years of U.S. Food Policy Response to Crises. CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute and Hunger Free America, 2021.

References

1. “The Impact of the Coronavirus on Food Insecurity in 2020,” Feeding America, October 2020.

2. Drennen et al, “Food Insecurity, Health, and Development in Children Under Age Four Years,” Pediatrics, October 2019.

3. Black, “Household Food Insecurities: Threats to Children’s Well-being,” American Psychological Association, June 2012.

4. Food Research & Action Center, “The Impact of Poverty, Food Insecurity, and Poor Nutrition on Health and Well-Being,” FRAC, December 2017.

5. Ammerman, Smith, and Calancie, “Practice-based Evidence in Public Health: Improving Reach, Relevance, and Results,” Annual Review of Public Health. March 18, 2014.

6. Tricco et al, “PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation,” Annals of Internal Medicine, October 2, 2018.

7. “State by State FNS Disaster Assistance,” USDA Food and Nutrition Service, December 2020.

8. Edwards, Mark, Colleen Heflin, Peter Mueser, Suzanne Porter, and Bruce Weber. “The Great Recession and SNAP Caseloads: A Tale of Two States.” Journal of Poverty. Vol. 20, 2016.

9. Nord and Prell, “Food Security Improved Following the 2009 Arra Increase in SNAP Benefits,” USDA Economic Research Service, April 2011.

10. Keith-jennings and Rosenbaum, “SNAP Benefit Boost in 2009 Recovery Act Provided Economic Stimulus and Reduced Hardship,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 31, 2015.

11. Ganong and Liebman, “Explaining Trends in SNAP Enrollment,” June 2013.

12. “Expanded Disaster Evacuee Policy,” USDA Food and Nutrition Service, September 14, 2005.

13. Shahin, “An Epic Disaster Required Unprecedented Response,” USDA Department of Agriculture, February 21, 2017.

14. Food Research & Action Center, “The FRAC Advocate’s Guide to the Disaster Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (D-SNAP),”FRAC.

15. Canning and Mentzer Morrison, “Quantifying the Impact of SNAP Benefits on the U.S. Economy and Jobs,” USDA Economic Research Service, July 18, 2019.

16. Sell, Zlotnik, Noonan, and Rubin. “The Recession and Food Security The Effect of the Recession on Child Well-Being,” PolicyLab, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, November 2010.

17. Richardson, “CRS Report for Congress Federal Food Assistance in Disasters: Hurricanes Katrina and Rita,” Congressional Research Service, September 23, 2005.

18. Seessel, “Responding to the 9/11 Terrorist Attacks: Lessons from Relief and Recovery in New York City,” A Report Prepared for the Ford Foundation, May 2003.