Introduction

A stronger, more integrated New York City and State regional foodshed offers many potential benefits: increased access to healthy affordable regionally grown food, creation of new good food jobs in agricultural and urban communities, better protection of farmland, more sustainable regional agriculture that slows climate change and new upstate /downstate partnerships that can constitute a political force for advocating alternatives to a corporate-dominated food system.

With so many benefits, who could oppose forging a stronger regional foodshed? In the real world, of course, change in the status quo always provokes opposition from those who benefit from current arrangements. In the coming months, the CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute seeks to engage a variety of constituencies in exploring the facilitators and obstacles to a stronger New York regional food shed. We’ll invite others to join us in describing and quantifying the benefits of a more regional approach to food policy, examining the potential for regional approaches to reducing the health and income inequalities associated with food production and consumption in the region, and forging new educational, advocacy and political approaches to growing our foodshed.

In this policy brief, we join this conversation by describing how three other North American cities have begun to grow their regional food sheds: Chicago, Toronto, and Cincinnati. New York is of course different: bigger, more diverse and perhaps more anchored in the global food system. But we believe each of these cities has useful lessons for New York. In the future, we’ll publish descriptions of other regional foodsheds. We invite your responses and your suggestions for other relevant bodies of experience.

Chicago

The story of regional planning in Chicago shows how regional food planning can be carried out by formal governmental bodies or by non-governmental stakeholders. As a result, planning can become a process that leaves room for different areas of emphasis, implementation strategies, and political orientations.

Go to 2040, chicago’s regional food plan

Around the country, various administrative bodies plan at the regional scale. For example, councils of governments, the associations of elected officials from the major municipalities in a region, can agree on policies and programs. Special districts or public authorities, the independent administrative bodies established to manage water, energy, or other multi-jurisdictional functions, can develop infrastructure that supports the regional food system. In Chicago, formal regional food planning was led by the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP), the region’s metropolitan planning organization (MPO). Metropolitan planning organizations are federally-mandated regional transportation agencies in every urbanized area of the US that plan, coordinate, review and approve transportation infrastructure. Most view their mission narrowly, though some like CMAP engage in comprehensive planning. As the MPO for the Chicago region, CMAP prepared a food systems report in 2009 that was incorporated a year later as a chapter on sustainable local food production in GO TO 2040. The plan was again updated in 2014 to propose a comprehensive regional plan to help Chicago, seven counties and 284 communities plan together for sustainable prosperity through mid-century and beyond.

Photo: GO TO 2040

The Planning Process

CMAP’s food planning process involved staff-led analysis and public consultations with regional stakeholders. The outcome was a focus on two issues that were particularly salient in 2010: increasing local food production (desired by suburban residents facing development pressure and the growing numbers of locavores) and the need to address food access in Chicago and other US cities. The strategies in the plan are now commonplace: dedicating land to urban agriculture; protecting agricultural land in the suburbs and exurbs; increasing the value of local food through institutional procurement; financing for new supermarkets; vouchers to enable SNAP participants to buy local produce; and data collection to support longer-term regional food system planning. Including them in a regional comprehensive plan was innovative. CMAP’s plan identified roles for non-profit, academic, and government sectors, calling for a regional food non-profit to continue analyzing and supporting food policies, coordination among other regional planning agencies, training and technical assistance for farmers, farm workers, and food businesses, and technical assistance by CMAP for county and city governments that wanted to include food and agricultural protection into local plans and ordinances.

On its own, GO TO 2040 did not change the Chicago foodshed, because CMAP has no authority over zoning, budgets, or local laws. Yet including a chapter on food in the plan elevated the importance of regional food planning and established a framework for policy development by local jurisdictions. For example, Chicago’s adoption of urban agriculture zoning and its food-focused neighborhood plan for the Southside community of Englewood were not caused by CMAP’s plan, but support for urban agriculture at the regional scale justified action at the city scale. CMAP also provided technical assistance to enable two urbanizing counties, Kane and Lake, to assess their remaining agricultural resources and develop plans to protect small farms. CMAP has committed to addressing food production and access in its forthcoming comprehensive plan, ON TO 2050, perhaps with different framing and emphasis.

Farm Illinois

Regional planning is not limited to planners and planning agencies, as the Food and Agriculture Road Map for Illinois (FARM Illinois) illustrates. In this example, it is the process of planning, rather than the adoption of a legally binding land use plan or policy that is of greatest interest. The main outcome is coalescing support around common goals, objectives and strategies. Planning skills are important to generate environmental, demographic, and economic data, but equally important is a method of involving stakeholders. This was the approach of the FARM Illinois project, an effort underwritten by the Chicago Community Trust that engaged food system thinkers from the non-profit, private, and public sectors to create a statewide food plan. In 2014, FARM Illinois established a leadership council to assess food system strengths and weaknesses at both a statewide scale and in Chicago. To do this, the council convened approximately 150 experts from the food and agriculture sectors, ranging from advocacy organizations to associations representing agricultural interests. Over nine months this group developed policy recommendations to promote agricultural innovation and address food insecurity, and in May 2015 published the FARM Illinois plan. While statewide in scale, the plan emphasized links between rural and urban communities, particularly the significance of Chicago in the state’s food system. The recommendations addressed several aspects of the food system: governance, calling for a statewide council for food and agriculture; business development, recommending new farm financing mechanisms, farmland succession planning, policies to foster “food clusters,” and support for entrepreneurs; workforce development, including food and agriculture training in primary and secondary schools and a university consortium to attract food-focused students and research projects; farmland and natural resource protection; food distribution infrastructure; and branding and marketing to boost the sales of Illinois food.

The most challenging part of planning, of course, is implementation. Plans adopted by government agencies that change zoning or map funded highway construction are less easily ignored than policy plans that require different entities to approve new laws, regulations, budget allocations, and infrastructure, and that reflect consensus at a particular moment in political time. Since 2015, FARM Illinois has continued to operate as a statewide association with a small staff that convenes stakeholders to identify opportunities to achieve the Roadmap’s goals and disseminates information about elements of the plan. The extent to which the plan comes to fruition depends in large measure on how solidly stakeholders are behind it and commit to adopting its recommendations.

Food: Land: Opportunity

A regional food plan can be something quite different than an element in a comprehensive plan or a report outlining needed policies. Philanthropies have increasingly engaged in a form of planning that is implemented through strategic funding. This was the approach that two philanthropies, the Kinship Foundation and the Chicago Community Trust, took as they developed Food: Land: Opportunity—Localizing the Chicago Foodshed. The initiative, launched in March 2014, aimed at creating a sustainable foodshed for Chicago through strategic grant-making (i.e., funding projects by invitation to align with a funder’s goals and objectives), an innovation competition, funded research, and stakeholder convening. The strategies included: increasing access to land for sustainable farming through new models of farmland acquisition and protection; strengthening food production by increasing the number of farmers and developing agricultural skills; and attracting capital to the food system through support for supply chain businesses, incentives for innovations to address supply chain inefficiencies, and an inventory of the foodshed.

Unlike conventional planning, which focuses mostly on governmental strategies, or stakeholder planning, which includes a mix of public and private efforts, Food: Land: Opportunity relies on private and non-profit sector innovations to shape the foodshed. For example, the foundation issued a challenge grant of $500,000 for innovative projects to address barriers limiting the scale of the local food sector, a priority for both CMAP and FARM Illinois as well. The notion was to encourage cross-sector teams to identify obstacles and opportunities, and in proposing a solution illustrate entrepreneurial and policy strategies to make the food system function more efficiently and equitably. In 2016, the grant was awarded to a team that plans to partner a Chicago-based non-profit (Top Box Foods) which distributes low cost, locally-produced fresh foods to low-income consumers, including SNAP participants, with a local farm network in Indiana (This Old Farm), and a technology platform to link the farmers and buyers with consumers at church pick-up locations and Chicago-area schools. While not a conventional plan element, the innovation illustrates many strategies and concepts that can be incorporated into policies and programs. Other grants include the Englewood Land Access Project, which helps neighborhood residents gain access to farmland within the Englewood Urban Agriculture Zone; a Good Food Business Accelerator, providing mentoring and support for entrepreneurs to launch or expand food businesses, and a Supply-side Food Systems Study to assess the Chicago region’s capacity to supply more local food.

Questions for New York City

- Who are the key stakeholders in the city, state and local communities who would have the commitment, knowledge and mandate to develop a regional foodshed plan?

- What existing regional public or non-profit agencies might serve as anchors for a New York regional planning process?

- How could a planning process—and a plan itself—overcome the traditional tensions between city and state governments?

Toronto

Toronto’s approach to food planning and community projects is influenced by a diverse set of stakeholders. It integrates the input of community organizations, retailers, urban planners, government employees, healthcare workers, farmers, food workers, manufacturers and a variety of knowledgeable activists to create one of the most innovative approaches to food policy in North America. A strong emphasis on local production, sustainability, procurement and consumption are central to the work in this city. Here are a few examples of some of the organizations, projects and policies currently shaping the Toronto food landscape.

Toronto Food Strategy (TFS)

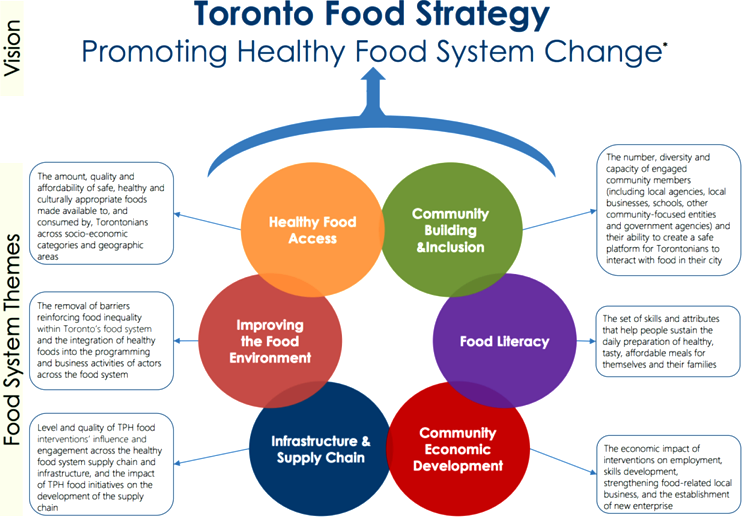

Toronto, like other growing cities, faces a diverse set of challenges around health, economic, social and environmental concerns that all play a role in the well-being of the city. Developing tactics to address these issues at a food-systems level is an approach that has gained traction with the local government over the last two decades. It’s this type of thinking that resulted in the creation of the Toronto Food Strategy, a municipal action plan for food projects and policies. Developed by Toronto Public Health (TPH) in 2008, it is refreshed every few years to ensure it addresses emerging needs and concerns. The Strategy, which is still overseen by TPH, is designed to help align the City of Toronto’s policies, with the goal of a healthy, sustainable food system that supports residents and community organizations in food solutions they want implemented in their neighborhoods.

The Toronto Food Strategy unit is housed within TPH’s Strategic Support Directorate and concentrates on realizing the strategic priorities detailed in the Toronto Food Strategy document. The team is funded from TPH’s budget, while its initiatives regularly receive external funding through public-private partnerships. The 2016 update to the strategy maintains six strategic goals: Healthy Food Access, Community Building and Inclusion, Food Literacy, Community Economic Development, Infrastructure and Supply Chain, and Improving the Food Environment.

There are several TPH supported projects underway aimed at achieving the Strategy’s goals. One of these is TFS’s Food Retail Environment Mapping initiative, which is developing a snapshot of access to healthy food around Toronto in order to identify opportunities where the City can work with neighborhood and private sector partners to expand access to healthy food. The Mobile Good Food Market, implemented in partnership with FoodShare and the United Way Toronto, looks for innovative ways to make healthy, affordable food available in more neighborhoods across the city in high need areas. As a kind of ‘produce store on wheels’ the market is able to limit its overhead cost and maintain the flexibility to move to where it’s needed. Another project, Community Food Works, uses a distinctive approach to linking safe food handling behaviors with nutrition education, employment support and other supportive skills for low-income residents in Toronto. TPH is also working with FoodShare, Parkdale Activity Recreation Centre (PARC), and the Ontario Food Terminal on their Aggregated Food Procurement initiative. This program works to improve the nutritional quality of foods served in community and social service agencies while also facilitating access to low-cost healthy food offerings. The Healthy Corner Stores program supports small, independent food retailers in lower-income neighborhoods through resources and strategies to increase their sales of healthier food. Lastly, TPH’s work with the Locally Grown World Crops project involves partnering with the Vineland Research and Innovation Centre and the Toronto Food Policy Council to explore opportunities for specific varieties of vegetables that are relatively new to local farms and that carry a regional significance to the more recent wave of newcomer Canadians, to be grown locally. Collectively these projects represent a uniquely cohesive approach towards realizing the core concepts detailed in the Toronto Food Strategy.

Bunz and GoodFood Help

A sprawling and unconventional community has emerged in Toronto based around a trading app called Bunz. As a networking platform Bunz allows its users to engage in non-monetary exchanges for goods and services. Users utilize Bunz Trading Zones as real life locations to coordinate transactions. Clothes, housing, and food are all exchanged via the platform. When it was initially launched 2013 by Emily Bitze as a Facebook group, Bunz attracted a small number of devoted users. It has grown into 53 groups, with trading zones in Vancouver, Brooklyn, Maryland and Tel Aviv, with much of the trading facilitated through the app. In Toronto some food security advocates are using the app to reach populations in need. One such group is GoodFood Help.

GoodFood Help was conceived in April 2016 when co-founder and director Kate Salter noticed a Bunz user’s requesting to trade for a banana. Her reply with an offer of food to the original user or anyone else in need of food assistance garnered a fair amount of attention, both from those looking for help as well as others who wanted to provide support. Inspired by the outpouring of need and support, GoodFood Help officially launched a few weeks later and immediately went viral in Toronto. The organization still actively uses Bunz, connecting with users posting requests and collecting alerts from others on the platform about those in need. GoodFood Help provides a service that complements other food security resources in Toronto. If someone experiences a brief episode of food insecurity, they may be unable or unwilling to visit a food bank due to fear, stigma or other barriers. In those cases GoodFood Help can fill in the gap. To obtain assistance GoodFood Help’s clients make a request and the organization works with them to deliver a food box in person, discreetly, at a transit station within 5 days, no questions asked. GoodFood Help provides a short-term solution for people in need and additional support in identifying resources for longer-term assistance if necessary.

GoodFood Help Box. Photo courtesy of Shannon Candido.

Questions For New York City

- Toronto’s non-profit organizations have played a key role in the development of regional food plans. Who are key nonprofits in New York City and State who could contribute to development of a regional plan? What incentives could bring—and keep—these organizations together in New York?

- How has the implementation of regional planning and action in Toronto contributed to reductions in inequitable access to healthy affordable food? What governance processes have supported—or blocked—this goal?

- What roles have growers and producers of food played in creating Toronto’s regional food approaches? What benefits has their engagement in regional planning brought them?

Cincinnati

In cities, towns, counties and states around the country, food advocates, governments and farmers have joined to create food policy councils (FPCs). These councils bring together the diverse constituencies that shape the food system to develop shared solutions to food security, farm policy, diet-related diseases, procurement, food waste and other issues. According to the Johns Hopkins University Center for a Livable Future, 293 food policy councils existed in the United States and Canada in 2016, more than 75% in the United States. In many, staff of local and state health departments plays a key role. The Greater Cincinnati Regional Food Policy Council is a food policy council that has made regional foodshed planning its top priority.

Photo credit: Ynsalh, Wikimedia Commons.

In Cincinnati, a city of about 300,000 people in southern Ohio, food policy proponents convened a food policy council that provides city, county and state health officials with a platform where they can forge partnerships with others, exchange ideas for improving food policy, and create and test innovative policies and programs. The Greater Cincinnati Regional Food Policy Council was created in 2015, an outgrowth of several years of city, county and state level efforts to coordinate food policy across sectors and borders. Its goal is to promote a healthy, equitable and sustainable food system throughout Greater Cincinnati’s ten-county region, an area that includes counties in Ohio, Kentucky and Indiana. Its forty members include farmers and food business owners; staff from city, county and state health departments and other public agencies; representatives of nonprofit groups and academics. The coalition is sponsored by Green Umbrella, a nonprofit alliance that supports regional sustainability. Brief descriptions of some of its activities illustrate the Food Policy Council’s range of engagement in the regional food system. Green Umbrella’s 2013 report, The State of Local Food in the Central Ohio River Valley, served as a needs assessment and roadmap for the regional council.

Subsidize Fruits and Vegetables

“Produce Perks” is an initiative that improves access to and affordability of fruits and vegetables for low-income consumers while also supporting the regional economy. Produce Perks increases the amount of fresh produce that SNAP or WIC recipients can purchase with their benefits. At participating farmers’ markets, customers using an Ohio electronic benefits transfer (EBT) card receive incentive tokens that provide a dollar-for-dollar match to every dollar spent on fruits and vegetables. The Cincinnati Health Department and its Creating Healthy Communities initiative partners with Ohio State University Extension, Hamilton County and Green Umbrella to administer Produce Perks. By 2016, the program had expanded to 11 farmers’ markets and a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) program. The Food Policy Council seeks to create additional public funding streams to expand the Produce Perks program regionally. In contrast to national food subsidies, which mainly benefit large scale growers of sugar, corn and soy, the building blocks of our unhealthy diets, Produce Perks uses public dollars to subsidize health.

Revitalize Public Markets

Public markets are permanent places organized by a public agency that sell primarily food year-round. The revitalization of Findlay Market in Cincinnati shows how several Food Policy Council members work together to create a sustainable regional food system. The market includes a public market, farmers’ market and farm stands, a farming internship program and a food business incubator with affordable licensed shared-use kitchen facility. It accepts SNAP / WIC EBT cards and participates in the Produce Perks program. It collaborates with the University of Cincinnati to film and distribute an instructional cooking video series promoting healthy tasty recipes. These programs boost local economic development, develop and support new and existing local growers, and strengthen the local food system by increasing access to and consumption of affordable healthy food.

Preserve Agricultural Land

Another goal of the council is to preserve agricultural land in order to ensure growers’ access to farmland in the 10 county region. To achieve this aim, the council supports legislation, ordinances, zoning and other policies that maintain and expand farmland and create public funding pools for farmland preservation programs. A few examples illustrate its intersectoral reach: the council has advocated for tax legislation that protects farmers when land valuation soar, alocal tax on sales that convert agricultural land to non-agricultural use, and state infrastructure investment that supports continuing agriculture.

In sum, the Greater Cincinnati Regional Food Policy Council has created a space where food growers, producers, environmental and health groups, and municipal, county and state governments can meet to coordinate policies that strengthen and develop the regional food system. In an earlier phase, the Ohio State government played an active role in sponsoring the Regional Food Policy Council, now it participates as a member. The council provides participants with access to the individuals and organizations that can forge intersectoral alliances across levels of government and jurisdictions. These partnerships can become concrete manifestations of the “health-in-policies” approach that the World Health Organization and others now advocate for improving health and reducing health inequities. In addition, the council provides a forum where stakeholders from the private, nonprofit and public sectors can consider the public interest in an environment where the power and privileges that the global food industry usually enjoys are somewhat constrained.

Questions for New York City

- What would an assessment of the New York regional foodshed need to include? How can existing reports such as New York City Food Metrics Reports, Scenic Hudson’s 2015 Foodshed Conservation Plan, the 2016 Five Borough Food Flow Report and others serve as useful starting points for regional food planning?

- What would be the advantages and disadvantages of creating a regional food policy council for New York?

- What processes might maximize the regional food and other benefits of the now mostly separate approaches to procurement, zoning and land use, farmland preservation, public food benefits, used by New York’s city, state and county governments?