Executive Summary

For more than a century, New York City has led the nation in using the authority and resources of municipal government to make healthy food, that most basic of human needs, more available, affordable and safer for all city residents. In this report, the CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute takes stock of what has changed in food policy in New York City since 2008. The goal is to provide evidence that can inform more equitable solutions to urban food problems in New York City and elsewhere.

Food Policy in New York City Since 2008: Lessons for the Next Decade seeks to answer several questions:

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the cumulative recommendations for food policy that New York City and State officials have made over the last decade?

- To what extent have the policies monitored through the New York City Food Metrics report since 2012 been implemented? What are the strengths and weaknesses of this monitoring system?

- What is the evidence on the implementation and impact of a broad array of public food policies that have been approved by New York City or State in the last decade?

- How have key nutrition and health indicators for the New York City population changed over the last decade? What do these changes tell us about the success and limitations of current food policies?

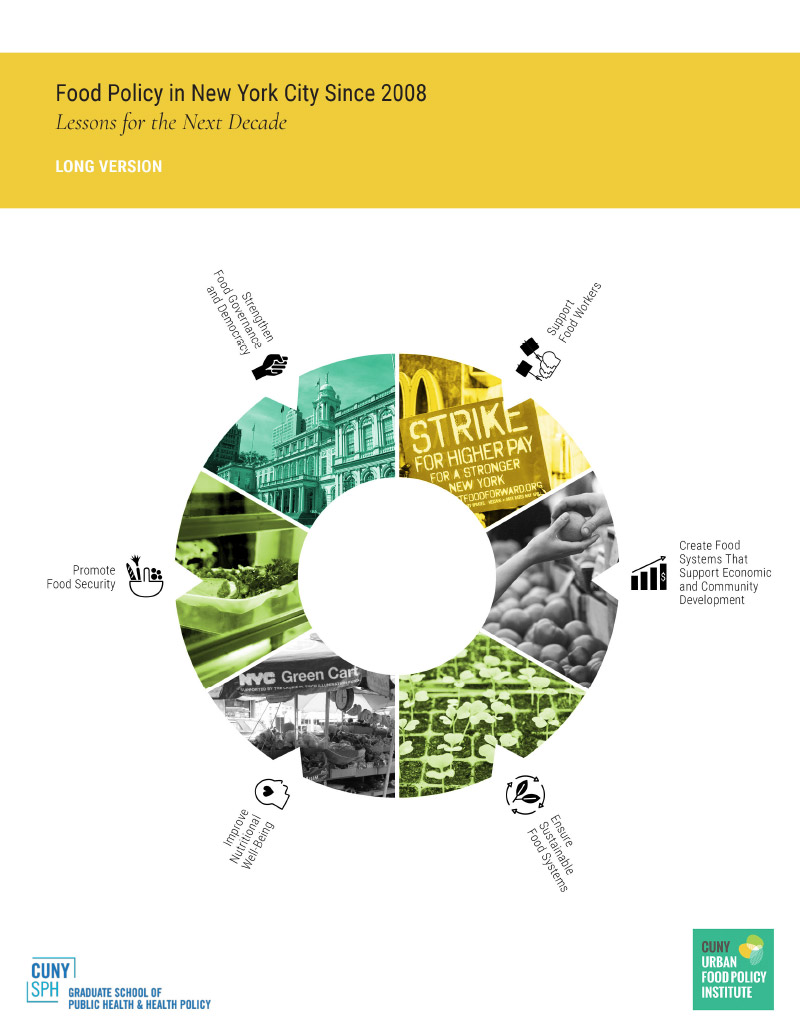

To find answers to these questions, we reviewed four public sources of evidence. First, we identified all major reports on food and food policy prepared by New York City and State public officials or agencies between 2008 and 2017. We identified 20 such documents with 420 recommendations, which we classified into six broad categories based on their primary goals. These recommendations proposed city and state policies to: (1) improve nutritional well-being; (2) promote food security; (3) create food systems that support economic and community development; (4) ensure sustainable food systems; (5) support food workers; and (6) strengthen food governance and food democracy.

Second, we reviewed the six annual Food Metrics Reports produced by the Mayor’s Office of Food Policy between 2012 and 2017 as mandated by a 2011 City Council law. We describe the findings, strengths and weaknesses of these reports, and examine changes that might make the metrics more useful for improving food policy in New York.

Third, to broaden our understanding of the implementation of city and state food policies, we identified 40 major city and state food policies implemented in the last decade and summarized available data on their implementation and impact.

Finally, we reviewed public data on five key health and social outcomes to analyze changes in New York City in these indicators over the last decade: fruit and vegetable consumption, sugary beverage and soda consumption, rates of obesity and overweight, diagnoses of diabetes, and the number of individuals meeting the USDA definition for food insecurity. Our analysis seeks to determine time trends in these indicators rather than to attribute observed changes to any specific policy.

Each of our methods and sources of data has strengths and weaknesses. By using multiple sources of data, this report provides a comprehensive overview of food policy change in New York in the last decade. Together the evidence presented constitutes the most thorough analysis to date of the food policy landscape in New York City over the last 10 years.

Key Findings

Improving nutritional well-being has been the most consistent food policy goal of city and state public officials. Goals that could benefit from greater policy attention and more involvement of diverse constituencies include reducing food insecurity, protecting food workers, and strengthening food governance and food democracy.

The six annual Food Metrics Reports show measurable progress on 51% of the 37 indicators and sub-indicator that are monitored, providing some assurance that a bare majority of food initiatives that the New York City Council selected for monitoring are moving in the right direction. However, these reports could be more useful to the food planning process by including more data, presented in ways that more clearly show progress or setbacks; disaggregating data geographically to enable communities to identify local problems; and made available in forms that facilitate further analysis by other public agencies, academics and advocates. Finally, most of the metrics chosen are outputs, not outcomes, limiting their value in determining whether monitored policies and programs are making a difference.

Our review of 40 policies that contributed to the six identified policy goals found that for each goal, a portfolio of city and state policies has been implemented over the last decade. For many, evidence demonstrates successful implementation. However, for the most part these policies and programs have not been designed or implemented on a scale likely to lead to meaningful changes in population or societal-level outcomes. These limitations point to the challenge of transforming food environments and reversing the many food-related problems that burden New York City residents and drive inequalities. The accomplishments in food policy to date do show that city and state governments can take action on food policy and implement policies that could lead to improvements in health if brought to scale and sustained and if design problems encountered in early implementation are addressed and partially solved.

The review of health and social outcomes over the last decade showed few or at best small increases in daily fruit and vegetable consumption, some reductions in sugary beverage consumption, persistently high rates of obesity and overweight with stable or widening inequitable distribution by race and ethnicity, modest increases in the proportion of New Yorkers ever diagnosed with diabetes and modest recent declines in the number and percentages of New Yorkers experiencing food insecurity. These findings suggest if New York City is to achieve meaningful improvements in food-related outcomes in the next decade, it will need to consider more than simply maintaining current efforts.

Recommendations

To develop feasible and transformative solutions to New York City’s food problems, we recommend:

- Create a New York City Food Plan that charts five to ten year food policy goals for the city, state, and region.

- Identify key outcomes and metrics for key food policy goals that can be used to monitor the food plan.

- Focus New York City food policies and programs more explicitly on reducing socioeconomic and racial/ethnic inequities in food-related outcomes and link to city equity initiatives on housing, employment, education, climate change, and zoning.

- Strengthen New York City’s public sector in food to better achieve public goals of reduced food insecurity and diet-related diseases and improved sustainability, food-related economic development, and improved pay, benefits and working conditions for food workers.

- Create new democracy and governance processes that offer New Yorkers a greater voice in shaping their food environments.

- Develop a collaborative food policy research and evaluation agenda that can fill gaps in knowledge and inform more effective and equitable food policy.