EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

More than 750,000 New Yorkers work in the food industry, making it one of the largest sectors in the city. Included in this workforce are fast food workers, grocery store cashiers, food deliverers, chefs, waiters, school cooks, workers in food manufacturing plants, and more. The food sector contributes significantly to New York’s economy, offering entry-level jobs with few formal entry requirements. During the COVID-19 pandemic, these jobs were deemed essential to the city’s wellbeing, ensuring our food supply. But despite being critical to New York City’s economy, the jobs in this sector pay below average wages, offer limited benefits, inadequately protect workers against health and safety threats, and generally offer few pathways to career advancement or higher wages. This is likely a key reason workers in the food sector were among those most likely to die or become ill because of workplace exposure to covid. Because people of color, women, and immigrants are overrepresented in New York City’s food workforce, the poor quality of employment in the sector contributes to the city’s most serious problems — growing inequalities in income, health, and living conditions by race/ethnicity, gender, and immigration status.

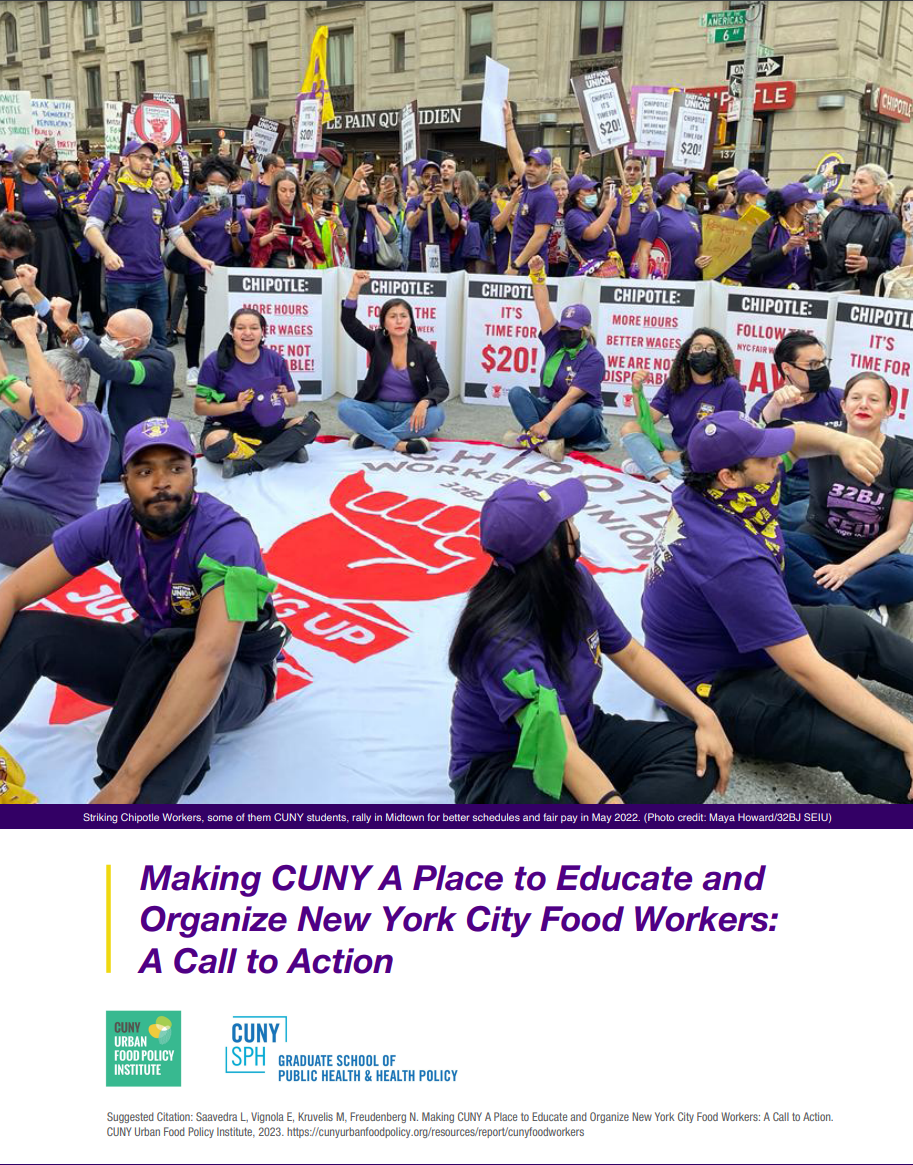

Recently, workers, the media, some public officials, and the public have begun to mobilize to improve the working conditions of food labor. In 2015, fast-food workers pressured New York State to increase the minimum wage for workers in their sector, and later, for workers statewide. Activism by food delivery workers led New York City to pass a package of bills aimed at improving the working conditions of food couriers. Recent efforts to unionize food workers at Starbucks, Chipotle, and Trader Joe’s locally and across the country illustrate the opportunity for improving the status of food workers.

City University of New York, the nation’s largest urban public university, enrolls more than 240,000 degree students and another 240,000 non-degree students. Through its academic programs, research, and workforce development activities, CUNY touches every community and every sector of the city’s economy. CUNY offers 28 food-related academic programs across 11 campuses, including certificates in catering and sustainable urban agriculture; Associates degrees in culinary arts, hospitality management, and food studies; and undergraduate and graduate degrees in hospitality, nutrition, dietetics, and food studies. No educational institution in the city prepares more people for the food sector than CUNY. Moreover, a recent survey of CUNY students found that an estimated 40,000 current CUNY students, about 16% of its degree students, work in the food sector, making it the largest single employment sector for our working students. Moreover, as Big Tech and finance cut jobs in New York and nationally, CUNY’s strategy of partnering mainly with these sectors to create high-end and STEM jobs for our students is called into question. Another strategy would be to improve jobs in sectors such as food and health care that will always be essential to New York City’s future.

This report make the case for CUNY to take on the role of training students to help strengthen New York City’s food workforce by ensuring that they know their rights, know how to exercise them in the workplace, and gain the skills needed to advance in this sector. Based on in-depth interviews with 20 CUNY students who are food workers, eight individuals who teach or lead CUNY food-related programs or who work for labor unions, and a review of recent academic and journalistic reports on the food industry in New York City, we identify several actions that CUNY could take to build a stronger food workforce for New York City. These include:

- Make CUNY a place where students who are food workers learn how to ensure that their employers protect their health and safety on the job, understand the benefits of unions, and can find opportunities inside and outside CUNY to advance their careers in the food sector.

- Assist CUNY students in balancing academic, family, and work demands in ways that support academic, economic, and life success.

- Create opportunities for unions and labor organizations to educate CUNY students about their services and the labor rights of working students.

- Engage food employers in assisting their workers who are college students to achieve their academic goals and support other workers seeking to continue their education.

- Establish a Food Workforce Development Task Force at CUNY to identify ways that the university, NYC government, employers, and labor unions can create a food sector that contributes to a thriving, equitable, and healthy New York.

AUTHORS

This report was prepared by the CUNY Food Workers Project, a collaboration of students and faculty from the CUNY School of Public Health (SPH), the CUNY School of Labor and Urban Studies (SLU), and the CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute.

The authors of this report are:

- Luis Saavedra, a Research Associate at the CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute and a student in the CUNY SPH Masters in Public Health program.

- Emilia Vignola, a Research Fellow at the CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute and a PhD candidate at the CUNY SPH. She is writing her dissertation on health threats of precarious employment among food workers.

- Melanie Kruvelis, a Research Associate at the CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute and a Masters student at the CUNY School of Labor and Urban Studies.

- Nicholas Freudenberg, Distinguished Professor of Public Health at the CUNY School of Public Health and founder and senior faculty fellow at the CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute.

Suggested citation: Saavedra L, Vignola E, Kruvelis M, Freudenberg N. Making CUNY A Place to Educate and Organize New York City Food Workers: A Call to Action. CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute, 2023.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the CUNY students, faculty, administrators, and union staff we interviewed for this report. Their words and thoughts are our sources , but we have kept their identities confidential. This project was supported by a grant from the Johnson Family Fund. Other contributors to the Institute’s work on the city’s food workforce include the New York State Health Foundation, Viking Global Foundation, Sachar Foundation, Tisch Illumination Fund, and Lily Auchincloss Foundation. We also thank Nevin Cohen, Craig Willingham, Katherine Tomaino Fraser, Rositsa Ilieva, and Eman Farris at the CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute for their contributions to this project and their comments on an earlier draft. The ideas and evidence presented in this report are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of our reviewers, employers, or funders.