Image Credit: foodsystemsdashboard.org

Can you briefly describe The Food Systems Dashboard and the motivation for creating it?

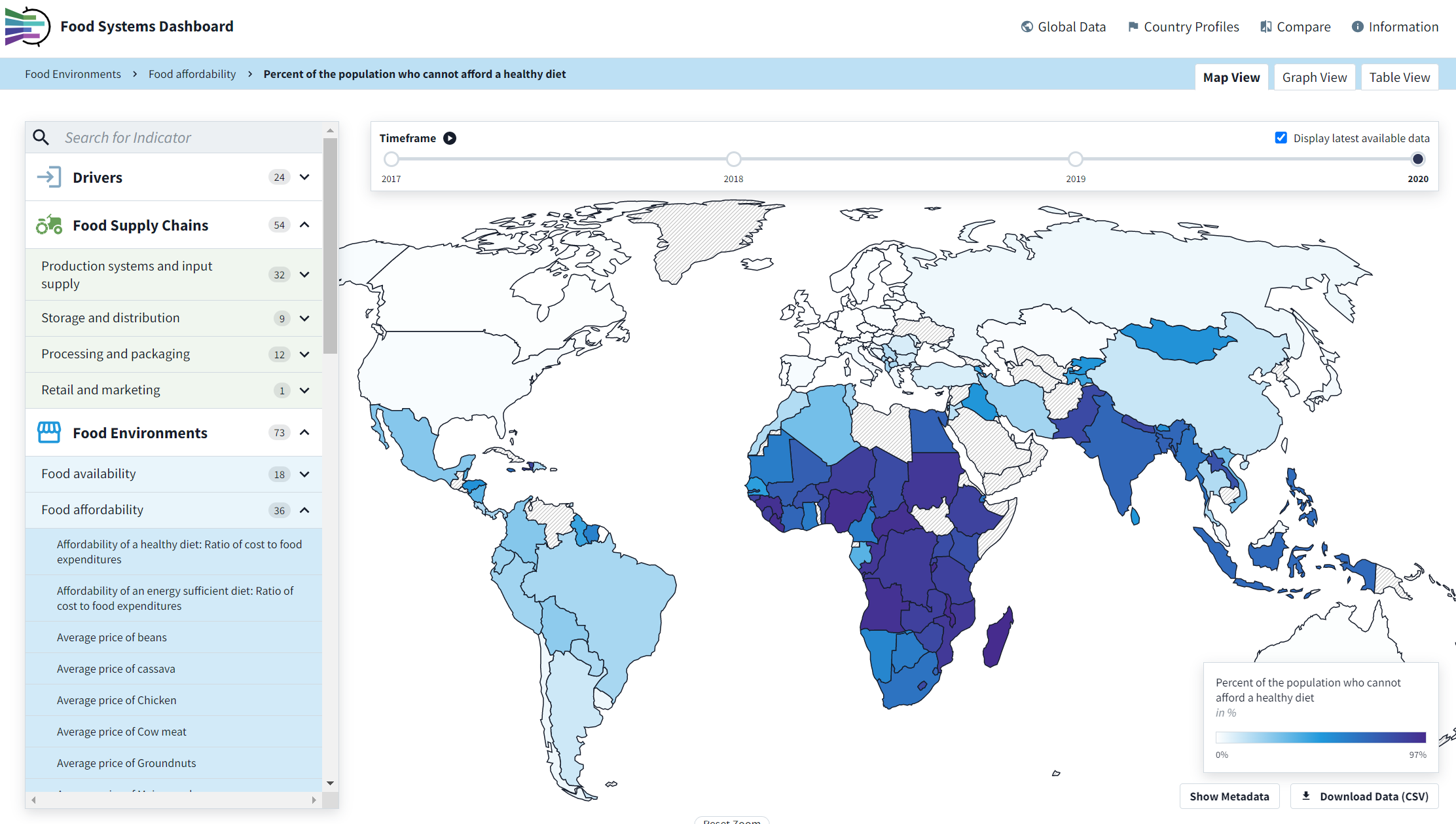

Rebecca McLaren (RM): The Food Systems Dashboard (FSD) is an innovative data platform that was launched in 2020 to provide a holistic look at food systems. Previously, food systems data were difficult to access and scattered across many different sources. Our motivation was to bring these data together and allow users to explore and understand interconnections across different areas of food systems, perform comparisons over time and between countries, identify key challenges and opportunities that may negatively or positively impact food systems, and inform decision-making to address these challenges. The FSD includes data on the drivers, components, and outcomes of food systems with over 225 indicators from over 40 different sources. These sources, which are both public and private, include United Nations agencies, the World Bank, the Consultative Group for International Agriculture Research (CGIAR), Euromonitor, and cross-country project-based datasets. Indicators are organized along the FSD’s food systems framework, adapted from the High-Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE). This framework identifies the different components that make up food systems, which are food supply chains, food environments, and individual factors. Within each of these components, sub-components have also been identified (e.g., food environments are characterized by food availability, food affordability, and several other sub-components). This framework also highlights the outcomes of food systems – diets, food security, nutrition and health, environment, economy, and social equity as well as environmental, social, economic, and political drivers – factors that push or pull the system in different directions. For each indicator, the FSD team has endeavored to articulate its specific relevance for human and/or planetary health within the indicator metadata that can be accessed by users.

The FSD has three sections – ‘Global Data’, ‘Country Profiles’, and ‘Policies and Actions’. The ‘Global Data’ section is meant to facilitate a deep dive into the data, allowing users to select any of the indicators and visualize them in a variety of ways including as maps, graphs, and tables. The ‘Country Profiles’ section is meant to provide a birds-eye view of a country’s food system by showing visualizations for 57 curated indicators selected by the FSD team to represent different macro-elements of food systems. This curated set of indicators is displayed as easy-to-interpret graphics for those less interested in manipulating data but instead interested in a snapshot of a country’s food system. Amongst these indicators are 39 diagnostic indicators, which have thresholds set by the team for classification as red (likely challenge area), yellow (possible challenge area), or green (unlikely challenge area).1 These diagnostics are included on the ‘Country Profiles’ in the ‘Diagnose and Decide Scorecard’. The ‘Country Profiles’ are meant to support country stakeholders’ efforts in using data to make informed decisions. The ‘Policies and Actions’ section currently includes 42 actions to improve nutrition and health as identified by a team led by Corinna Hawkes.2 We are currently in the process of adding an additional 45 actions focused on improving planetary health.

How did you decide what food system metrics or indicators to include in the dashboard?

RM: Achieving our objectives requires that the indicators included on the FSD are relevant and of high-quality, among other criteria. The first criterion for a potential indicator is that it should clearly map to a specific component and subcomponent of our conceptual framework. This is essential for the first objective of the FSD, to describe food systems. Our goal is to identify at least two indicators for each subcomponent in our framework; however, gaps remain related to individual factors and environmental, economic, and equity outcomes. Each indicator should furthermore be unique among the other indicators included in the FSD.

Another key service provided by the FSD is the curation of high-quality indicators. Quality is interpreted as the extent to which an indicator provides an unbiased measure of a component of food systems. Validity studies are rarely available for food systems-related measures, especially for those addressing food supply chains and food environments. Therefore, we rely mainly on the opinion of experts, including those on the FSD team and partners with specialized knowledge. As part of the quality assurance process, the team reviews the methods used to collect data for potential indicators and the calculation of those indicators. Therefore, indicator calculation methodology must be transparent. Prioritization is given to indicators that have been included in open access databases, grey literature reports, or peer-reviewed publications that describe the methodology used. Attention is given to the sampling procedures and any possible sources of measurement error.

Another criterion is that potential indicators should have significant geographic coverage. In addition to being necessary to describe global food systems, having good country coverage enables comparisons between countries, as well as between and within regions, food system types, and income classifications. These comparisons facilitate the diagnosis of challenge areas and highlight opportunities that countries may have in relation to others. As a general rule, indicators that are available for fewer than 50 countries are excluded. Most indicators currently on the FSD are available for over 100 countries. We also prioritize indicators that represent low, middle, and high-income countries more or less equally. Similarly, we prioritize indicators that are available for all regions of the world and for which country coverage within individual regions is at least 50%.

The FSD also prioritizes indicators that are as up to date as possible; therefore, indicators for which the most recent data is over ten years old are typically excluded. We prioritize indicators that have a high likelihood of being updated frequently; therefore, many indicators are drawn from well-established databases such as the Food and Agriculture Organization Food Balance Sheets and World Bank Databank, which are often updated on an annual basis.

Each indicator is assessed on the balance of all these criteria and does not need to meet each one of them. Moving forward, we welcome recommendations for indicators to add and collaboration with new groups. Requests to add indicators will undergo a review from our team. Indicators that undergo review and meet our established criteria will be added to the FSD.

What were some of the most challenging aspects the team faced during the dashboard development? (e.g., incomplete or unavailable data, inconsistent collection, etc.)

RM: Our team has faced many challenges in creating the FSD. Capturing the complexity of food systems requires a large number of indicators and there are areas of our framework that are still empty. In some cases, this may be because no indicators exist; however, there are also indicators that are privately held. This is especially true of indicators that cover consumer behavior, within individual factors. Additionally, other indicators are only available in a small number of countries, in one region, or for one income classification. For example, several food safety indicators are only available for high-income countries in Europe and thus are not included on the FSD.

Who were the primary intended users of the dashboard and who is using it now?

RM: The FSD is intended for several different audiences – policymakers, practitioners, researchers, and educators across the world. The different sections of the FSD are tailored to different users with the ‘Global Data’ section designed more for researchers and the ‘Country Profiles’ section more for policymakers. While we have received feedback that each of these groups is using the FSD, we have also received feedback on some of the limitations different users face. The FSD is only available in English, but we are working on translating the site into Arabic, Chinese, French, Hindi, Russian, and Spanish. This will allow the FSD to reach a wider global audience. The FSD also only has national level indicators, while most policymakers need subnational data for decision-making. We are incorporating subnational data in upcoming country dashboards, as discussed in more detail below.

The Food Systems Dashboard was initially launched in 2020. Can you share any examples of how someone used the data from the dashboard to influence a specific food systems program or policy?

RM: The FSD team always welcomes feedback, and we are especially interested to hear how the FSD is being used. The World Bank used the FSD in a pilot exercise in 2022 to provide their teams with Diet and Nutrition Profiles to support project design in the Country Climate and Development Reports and Systematic Country Diagnostics. They used the FSD ‘Country Profiles’ as a starting point and added other relevant data from the FSD as well as subnational data. In the first pilot exercise, profiles were made to inform projects in Ethiopia, Uganda, and India.

The European Alliance for Agricultural Knowledge for Development used the FSD in work implementing regional food nutrition programs across Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius, and Seychelles. They used the FSD to explore the context in each country, providing feedback that the ‘Country Profiles’ were especially useful for this purpose. They also used the FSD to support evidence-based activities and targets and inform program and project level monitoring and evaluation.

In what ways do you think a dashboard tool, instead of a more traditional report, can inform smarter and better food policy and planning?

RM: Our aim is for the FSD to provide policymakers and practitioners with the information they need for evidence-based decision-making. The data are the focal point of the FSD, and the dashboard platform is interactive and dynamic, allowing users to find the most up to date information that is relevant and useful for their objectives. The FSD is continually updated, with new indicators added and existing indicators updated when available, which is not possible in static reports. Additionally, we continue to add new features and tools such as the diagnostics discussed above.

The current dashboard focuses on representing global, regional, and national food systems. What are some of the opportunities and challenges for developing dashboards at other scales such as municipal or metropolitan ones?

RM: There are many opportunities with global dashboards such as the FSD, including allowing comparisons between countries, regions, and food system types. However, global dashboards also have limitations. Subnational data are key for decision-making, feedback that we received from stakeholders using the FSD. Our team is currently working on country dashboards that will include subnational data at different administrative levels. These country dashboards are first being developed in Bangladesh, Indonesia, Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, and Pakistan with the aim of expanding to more countries. These country dashboards provide the opportunity to include more indicators that may not have had the geographic coverage to meet the criteria for inclusion in the global FSD. They also provide the opportunity to display data collected in countries at a more granular level, which is the data used by national and local decision-makers to define their investment priorities and design their policies, strategies, and action plans.

Can you share what are some of the next steps for this work?

RM: We are continually improving the FSD user interface and have plans to improve existing features as well as add new ones. We are in the process of updating the FSD framework to move consumer behavior as a subcomponent of individual factors instead of its own component. The user experience will also be improved by making the graph and compare views more intuitive and powerful and adding several new features, including adding tags to the indicators, such as for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and planetary boundaries, and more options for downloading the data. This will add new dimensions to how the indicators are organized and can be viewed.

The FSD team continues to evaluate new indicators. The Food Systems Countdown Initiative (FSCI) is a complementary initiative developed to meet separate but related global needs. The FSCI aims to build a science-based observational system, identifying high-quality food systems indicators to measure, asses, and track the performance of food systems towards 2030 and the conclusion of the SDGs. Many of these indicators are already on the FSD, but the remainder will be added. We have also been working with the GAIN EatSafe project (a USAID Feed the Future-funded multi-country food safety project) to identify a set of food safety indicators to add.

We will continue to develop country dashboards populated with subnational data in Bangladesh, Indonesia, Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, and Pakistan, and work closely with national governments to ensure their uptake and sustainability.

We plan to add to and redesign the ‘Policies and Actions’ section to be more aesthetically pleasing and have more functionality. Additionally, we are exploring the possibility of adding to the diagnostic work by developing benchmarks that would compare one country’s diagnostics to others that are similar in terms of region, food system type, or income classification. We are also exploring the possibility of developing a prognostic tool for the Dashboard that would project how indicators may behave into the future.

Another area of work being done in partnership with the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab is to investigate the impact of shocks – climate change-related extreme weather events, geophysical disasters, political upheaval and conflict – on food systems. We are currently exploring different models of shocks and will use this, in conjunction with a wider correlation analysis, to create a systems dynamics model to investigate how these shocks impact food systems.