The pandemic has been a harsh teacher for food justice advocates. We have seen long-term goals grab renewed public attention, win additional resources, and spark more sustainable solutions, only to have these new opportunities fizzle away as policy maker and public attention turns elsewhere. At the CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute, we have been working to illuminate the struggles and needs of low wage food workers since our founding in 2016. The pandemic has highlighted the low wages, limited benefits, health and safety hazards, and financial insecurity of food workers and their families across the supply chain. But we worry that we need to do more in the food justice movement to realize new opportunities to solve these persistent problems.

In this commentary, we summarize nine lessons we have learned from the pandemic about improving conditions for food workers. We extract these lessons from our own experiences, in particular a recently released report, a policy brief, and a Grand Rounds presentation sponsored by our institute, all related to food labor. We also draw from our synthesis of the growing academic, journalistic and advocacy work on the food workforce.

1. Define “essential workers” in ways that translate into new rights and benefits.

Early in the pandemic, many elected officials and the public at large realized that food workers, like health care and public safety workers, were essential to keeping our society functioning. But this insight did not lead to higher pay, better health and safety standards, or more access to personal protective equipment. To make the term “essential worker” meaningful, our society must confer benefits that enhance the dignity, power, health and pay of these workers.

2. Low-wage food workers need higher wages and benefits – as well as higher quality employment.

Employment quality refers to the relational and contractual aspects of employment. Recent scholarly work identifies seven dimensions of employment quality that affect worker well-being: employment stability, material rewards, rights and protections, work time arrangements, opportunities for training, collective organization, and interpersonal power relations. The quality of employment across the food sector is generally quite poor, also referred to as precarious, due to high job insecurity, few rights, frequently unstable schedules, and little power on the job. As the pandemic led to mass layoffs of food workers, unannounced changes in work schedules, high exposure risk to COVID-19, and rising financial insecurity, a narrow focus on pay and benefits failed to account for the myriad ways that precarious employment affects both the physical and mental health of food workers. As food justice advocates, we should seize the opportunity to advocate for higher quality employment more broadly. This includes protecting workers (mis)classified as independent contractors, exemplified by the new laws on app-based food delivery workers in New York City and elsewhere.

3. Racism and misogyny are critical obstacles to improving the lives of food workers.

Most low wage food workers are Black, Latinx, or other people of color, recent immigrants and/or women. Their overrepresentation in the lowest paid occupations and industries of the food system imposes a double burden — the low pay, limited benefits and unsafe conditions of their work, and the legacy of policies, hierarchies and business practices that perpetuate racial, gender, and other inequities in the workplace and beyond. The disproportionate burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on communities of color in general and low wage food workers in specific illustrate the cumulative impact of intersecting systems of oppression. Just as the food justice movement fights racial gaps in access to healthy food, we should support efforts to increase minimum wages as a step towards racial equity.

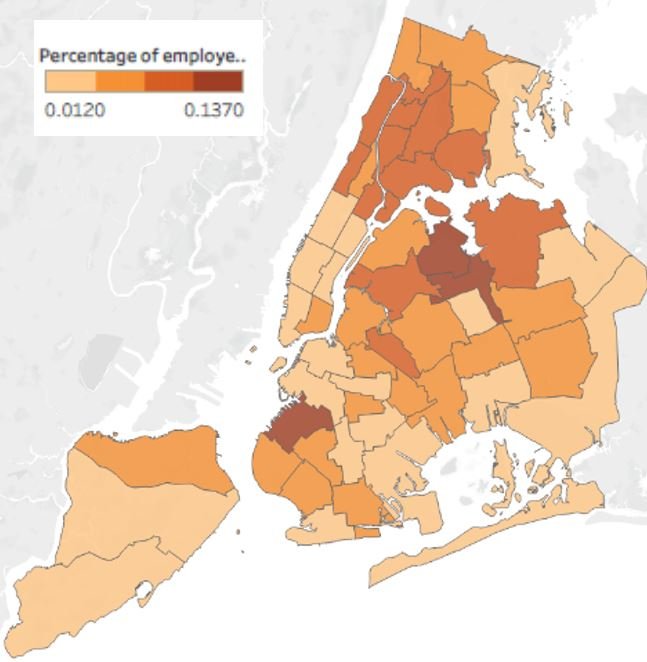

Percent of Employed Population in Food Preparation and Serving by New York City Neighborhood. This map show that the proportion of food service workers are highest in the city’s Black, Latinx and immigrant neighborhoods, suggesting the potential for linking campaigns to promote racial and labor justice.

4. Food workers have mental health needs as well as health and safety needs.

In the past, occupational health specialists have focused on the physical impact of workplace injuries and toxic exposures, risks that remain prevalent in many food jobs. The pandemic has exacerbated the negative effects of precarious employment, especially related to job insecurity. The social isolation imposed by the pandemic and the new burdens of juggling work and childcare responsibilities worsened the mental health of food workers, also harming workers’ families. Comprehensive efforts to improve food worker well-being should take on the psychological consequences of precarious employment as well as the physical consequences of workplace hazards. Yet another reason to tackle isolation and mental health problems is that these conditions can make it more difficult for food workers to join unions.

5. Making food workers more visible can win public support for fairer policies.

Labor unions and worker advocacy organizations, such as the United Food and Commercial Workers and the Food Chain Workers Alliance, led public campaigns to tell the stories of food workers hurt by the pandemic. We must find new ways to make these personal narratives public and to sustain the political support they generate. These stories can help attract policy maker and public attention, as illustrated by a proposal for city government to create a “resources center” for gig economy workers like deliveristas, who bring food to people’s homes.

6. Integrating occupational health with public health benefits workers, their families, and all of society.

Our health is shaped by our education, physical environment, health care, and diets — and our work. The pandemic showed how employment and working conditions of food workers increase their risk of mental health problems, infectious diseases, and injury as well as their ability to balance family and work life. Integrating occupational health with public health and primary health care will enable public health professionals and health care providers to help workers and communities prevent exposures, ensure vigorous enforcement of occupational health laws, and identify and treat work-related health problems before they lead to disability. In the food sector, this will require developing strategies to reduce the specific health risks in each industry of the food workforce, from agricultural workers to food deliverers, and to make explicit how these risks are public health issues that concern all of us.

7. To win improvements in work quality, pay and benefits, food workers need to be able to join unions.

Labor unions protect workers by winning better wages and benefits, promoting workplace health and safety, advocating for other labor laws and social policies, and protecting workers against arbitrary firing or discipline. New laws such as higher minimum wages, those banning wage theft, and mandatory sick pay result from advocacy by worker organizations and require adequate funding and ongoing union pressure for enforcement. By finding new ways to support and facilitate food workers’ growing interest in joining unions, public health professionals and food justice advocates can contribute to improved conditions and better health for low wage food workers. Unions also need to find new ways to engage workers, speak to their identified needs, and develop new metrics to measure their success.

8. Improving the lives of low wage food workers requires increasing their access to the necessities of life beyond work.

By partnering with those working for affordable housing, universal access to health care, and quality education, food justice advocates can contribute to creating a movement that has the power and vision to improve the lives of food workers — and all New Yorkers. At our Institute, we are exploring new roles CUNY can play in helping our students who are also food workers to learn their rights, join unions, and advance their careers. Aligning food policy with other equity-oriented social policies increases its impact.

9. Food and labor are ideas that can bring together individuals and movements across issues and sectors.

Until recently, the food movement failed to make the needs of food workers a priority, while the labor movement did not see food and diet as central political questions. The pandemic has highlighted the potential to link food system change and the need to improve workers’ lives as unifying ideas to build more powerful alliances for promoting health, equity, and justice.

In the coming months, we at the CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute invite food justice and labor advocates, public health professionals, and others to join us in translating into practice these ideas to make food workers essential partners and beneficiaries of the food justice movement.

By Emma Vignola, Luis Saavedra, Katy Tomaino Fraser, and Nicholas Freudenberg from the CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute at the CUY School of Public Health

For more information

Chong VP, James CJ, ; Fraser, Tomaino K; Brown R, Ignacio K, Willingham Craig, Cohen N, Freudenberg N, Protecting Those Who Feed Us: How Employers, Government, and Workers’ Organizations Can Protect the Health, Safety, and Economic Security of Food Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond. CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute, March 2022.

Fraser KT, Vignola EF, Chong VP, Ng Y, Ilieva RT, Willingham C, Cohen N, and Freudenberg N. Ensuring All NYC Food Workers Have Safe Working Conditions, the Right to Organize, and Sufficient Pay and Benefits. New York Food 2025, a collaboration of Hunter College NYC Food Policy Center; Laurie M. Tisch Center for Food, Education & Policy, Teachers College Columbia University; and CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute. March 2022.

Freudenberg, N., Silver, M., Hirsch, L., & Cohen, N. (2016). The good food jobs nexus: A strategy for promoting health, employment, and economic development. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 6(2), 283–301.

Gaitens J, Condon M, Fernandes E, McDiarmid M. COVID-19 and essential workers: A narrative review of health outcomes and moral injury. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(4):1446.

Henderson K. The crisis of low wages in the US Who makes less than $15 an hour in 2022? Oxfam America, 2022.

Nebeker R. We Need to Better Protect Food and farmworkers During COVID-19 And Beyond. Foodprint, 2/26/21

Tsui EK, Franzosa E, Vignola EF, Cuervo I, Landsbergis P, Zelnick J, Baron S. Recognizing careworkers’ contributions to improving the social determinants of health: A call for supporting healthy carework. New Solutions. 2021;1-10.

Willingham, C., Flechsig C, Freudenberg N. A Guide to Growing Good Food Jobs in New York City. CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute, 2018.

<a href=”https://www.laborpress.org/study-confirms-new-york-city-deliveristas-are-underpaid/” target=”_blank” rel=”noopener”><small>Main image credit</small></a>