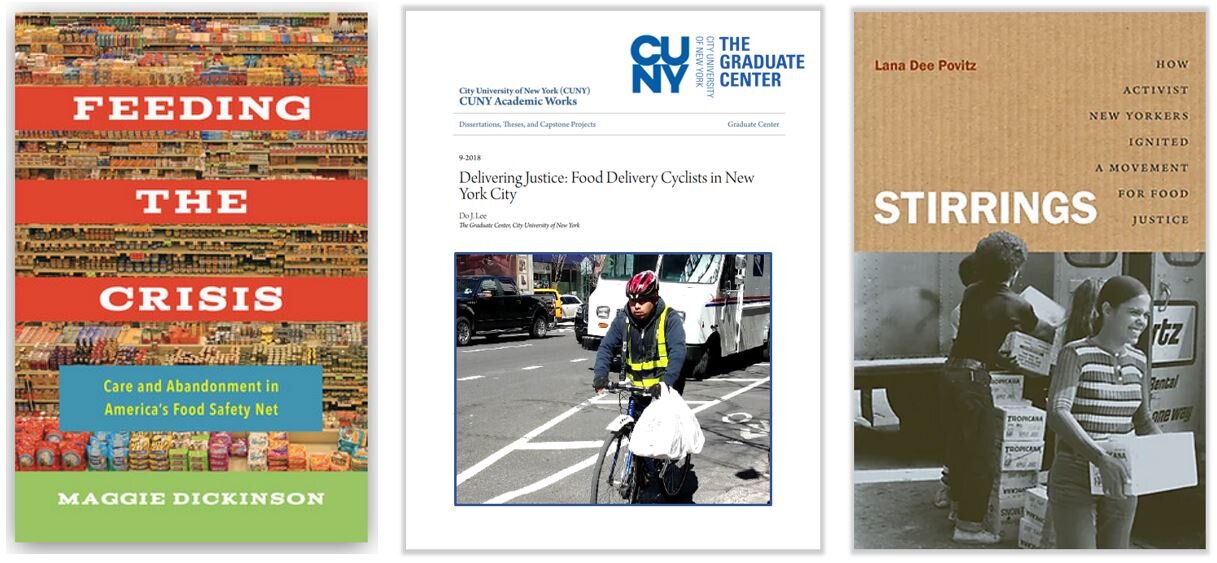

Left to Right: Maggie Dickinson (Assistant Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies, Stella and Charles Guttman Community College, The City University of New York), Do Jun Lee (Assistant Professor, Department of Urban Studies, Queens College, The City University of New York), Lana Dee Povitz (Visiting Assistant Professor of History, Middlebury College)

In preparation for the CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute’s February Urban Food Policy Forum on “Food Equity Research in New York: Fresh Perspectives,” the CUNY Urban Food Policy Monitor reached out to scholars and authors of recent research monographs exploring the topic from different angles and disciplines. We asked them to share their insight on the role of academics in advancing food justice in New York, the ways they balance their roles as food equity academics and activists, as well as how they incorporate food equity knowledge from their scholarship into the classroom. Here are their recent publications and what they shared on these questions.

L to R: Feeding the Crisis: Care and Abandonment in America’s Food Safety Net (University of California Press, 2019); Delivering Justice: Food Delivery Cyclists in New York City (City University of New York, 2018); Stirrings: How Activist New Yorkers Ignited a Movement for Food Justice (University of North Carolina Press, 2019)

Food Policy Monitor (FPM): In your view, what is the role of academics and researchers in analyzing food policy and food justice, or in using food as a prism to analyze social justice questions?

Maggie Dickinson (MD): I think some of the most valuable work academics and researchers can do is to help us rethink our assumptions around questions of food policy and social justice. Jan Poppendieck’s work on charitable food is an excellent example. Soup kitchens and food pantries seem unquestionably good, and yet she shows how their proliferation had serious consequences for how we understand both the causes of hunger and how we as a society should address the issue. Solutions to problems like hunger emerge from a complex interplay of social, economic, and political interests. Researchers have the time and the resources to untangle these threads. Doing so can open up new ways of thinking about power and justice in the food system.

Do Jun Lee (DJL): Food is often a powerful way to understand how we all relate and connect to each other. For example, whenever I begin a presentation on our participatory action research with immigrant food delivery cyclists, I ask the audience who has ever ordered or eaten food that has been delivered. Usually, everyone raises their hands and by doing so, we recognize how we are mutually implicated in producing a system of food delivery and its injustices. Food justice as a nexus of connections and relationships means that researching and acting upon the messy complexity of food delivery cycling requires what bell hooks calls a “community of resistance” to the language and systems of oppression that excludes the voices, perspectives, and knowledge of those marginalized such as immigrant delivery workers. By listening to workers, our community of resistance of scholars, practitioners, activists, delivery workers, artists, journalists, legal and policy experts, and many others began to be able to understand and reframe food delivery not in the power-laden public narratives of safety that unfairly scapegoated workers, but rather in terms of unequal power relations such as informal labor conditions, global capital and human migration, discriminatory policing, non-inclusive policy and lawmaking, and unsafe streets.

Lana Dee Povitz (LDP): Historians can probably play a useful role for policymakers, analysts, and activists when we provide critical context for issues that might seem new, and when we offer examples of strategies and tactics that may have worked particularly well, or that were not especially successful. As academics, we can also use our institutional resources to illuminate activist campaigns that we think are worthwhile. Food also can be a way ‘in’ for people to understand how social justice concerns are all related. The same people who need food also likely need access to health care, housing, financial assistance, and a safe environment.

FPM: How do the roles of academics and journalists working on food equity overlap? How are they different?

DJL: One of the important ways to work on food equity is to challenge harmful public discourses that get reproduced and justified as common sense. We found that it is enormously difficult (albeit possible) to change public narratives that thrive in unequal conditions, such as wealthy, privileged residents complaining about immigrant food delivery workers who bring them food. But at the same time, we also found many people who welcome and act upon learning counter-narratives with evidence. As academics, it is our responsibility to examine what fuels harmful narratives and to participate in the public discourse to complicate narratives with the evidence we find. In our research, we found that nearly three quarters of media stories about food delivery workers did not have a quote by a food delivery worker – meaning that other more privileged people were defining delivery workers and often to their detriment. Through our participatory research with workers, our research findings helped provide evidence that helped journalists better incorporate immigrant worker voices and perspectives to complicate and change public narratives in media stories.

LDP: There can be considerable overlap, although journalists typically are under more of a serious time crunch than academics to conduct research and write up their findings. We academics often have the luxury of studying a subject for months or years, and I think this can allow us to tell more nuanced and careful stories, and to have a stronger sense of what work has already been done. I would also say journalists are trained to write for a reading public, whereas academics do not always focus so much on the quality of their prose.

FPM: How do you balance your commitment as an academic scholar with your role as a public intellectual, or researcher activist, invested in producing evidence that serves to address and eliminate food injustices?

MD: I don’t really differentiate my roles as an academic, a public intellectual, and an advocate. For me, they are all one piece. My commitment to eliminating injustice – including food injustice – guides my research agenda. I choose to work on issues like SNAP policy that I think are important for everyday people. Part of my research process for my book Feeding the Crisis was going to the welfare office to try and help people get benefits or to argue with welfare office workers when people’s benefits were cut. The research process is never really neutral and so I think it is better to be up front about the ethical commitments that guide our work. These are the same commitments that guide my decisions about writing for the public. When the Trump administration announced it was cutting 700,000 people from SNAP in December by tightening work requirements, I wrote several public pieces based on my research to push back against the policy of tying food assistance to work.

DJL: From my readings on the topic of collective liberation and decolonization, an essential step in these processes is to be able to name, characterize, and educate each other on the histories, systems, and structures of oppression that we live within so that we can act with intent toward shaping a more just society. I think for myself, approaching scholarship in this way means that being an academic scholar is aligned with being a researcher activist on a personal level. However, my experience is also that the demands of our system of academic scholarship can often come into conflict with research activism, particularly because the activism piece is highly labor and time intensive. But research activism itself is also a site of important knowledge production while helping us to think critically about what our research does in the world.

LDP: I don’t see my research as activist, but I do think that as educators we have an important role to play in helping those we teach to understand what is possible when people work collectively. Professors are often automatically accorded respect, so we have the opportunity to center marginalized voices and perspectives that are usually excluded from public education in this country. For those of us who have activist experience, we can also mentor students who are trying to disrupt business as usual and connect them to other organized efforts already afoot. We can write and teach in ways that build solidarity—the ability to see ourselves in others and understand our interdependency—and that maintain a big tent. It is very important not to become single-issue or to throw certain people under the bus in pursuit of political change.

FPM: In what ways do you interact with other food and health professionals and what roles do they play, or could they play, in helping you navigate food policy and food justice?

MD: I have learned a tremendous amount from people doing anti-hunger work in New York City. People doing this work at the Food Bank for New York City trained me to do food stamp outreach, which has been integral to my research process – especially for learning how food policy is actually carried out and enacted in welfare offices. I’m working on a project right now about the barriers to SNAP enrollment among college students. Again, it is the people who work at Single Stop and in the food pantries at CUNY who are teaching me about the real challenges that make it hard for our students to get the help they need. They are the real experts on food policy and a lot of what I do is simply gather that wisdom and amplify it in ways that can, hopefully, have an impact on policy. The people who do this work often care very deeply about making sure people have access to the healthy food they need to thrive. My goal as a researcher is to use my time, resources, and privilege to push for systemic policy changes that professionals need to do that work well.

FPM: How does your scholarship relate to your teaching practice at your university? Can you give an example of a course, or a course assignment, in which you have incorporated food justice learning goals?

MD: I love teaching about food because students are always able to connect to this topic. As an anthropologist, I often use food as a lens to think about the relationship between food, culture, and power. I want students to understand that food is always political. I have a project where students research the origins of a particular food culture. They often choose to do research on their own cultures – which is often a very affirming experience for them. Through food, they are able to explore the impact of immigration, enslavement, colonialism, industrialization, and access to land on the kinds of food they grew up eating. Thinking about the foods they love, like Guyanese curry or Italian American dishes like spaghetti and meatballs, gives them a way to engage these big questions that might otherwise feel too big, too overwhelming, or too abstract.

DJL: One teaching practice I use is to have students engage and experiment with everyday life in order to better understand the systems and structures that support some behaviors while suppressing other actions. For instance, in classes about sustainability, I had the students do a personal sustainability project in which they have to adopt for two months one totally new habitual behavior that could be rationalized as more sustainable. I stress to the students that this project is not about individual success or failure but rather to observe the systems and structures that help and hinder them and to examine why. For many students, they often picked food-related projects such as eating vegan or vegetarian, eating more locally sourced food, growing food, or composting food waste. This project is scaffolded with a research paper where the students research the implications and complexity of social justice in their project. In the course of the projects, students begin to experience challenges that lead them to ask and investigate questions such as neighborhood differences in food access or resources or to even interrogate the definition of sustainability and who gets define it.

LDP: I teach a course on the history of US food activism. One of the things I focused on in my book, and which I really emphasize in teaching is well, is that we can never lose sight of hunger and other forms of food injustice as, at root, poverty problems – that attacks on people’s right to food are attacks on their ability to experience economic justice. I also make sure to show the incredible variety of social justice efforts that can be encapsulated by “food justice.” The Black Panthers and Young Lords fought white supremacy by providing free breakfasts to local children; housewives used boycotts of meat to protest the rising cost of food prices across the country; countercultural New Leftists started food coops as a way of embodying the democratic practices they wanted to see in the wider world.

FPM: How can our readers learn more about your work and support your research?

MD: My book Feeding the Crisis: Care and Abandonment in America’s Food Safety Net just came out from the University of California Press. I’m excited for people to read and engage with it. I tweet about food policy a lot. People can follow me there at @mag2d2.

DJL: My Twitter @dosik and my website: www.intersectionalriding.com

LDP: Google me! :)

Interview by Rositsa T. Ilieva, Director of Food Policy Monitor, CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute