Food Policy from Elsewhere

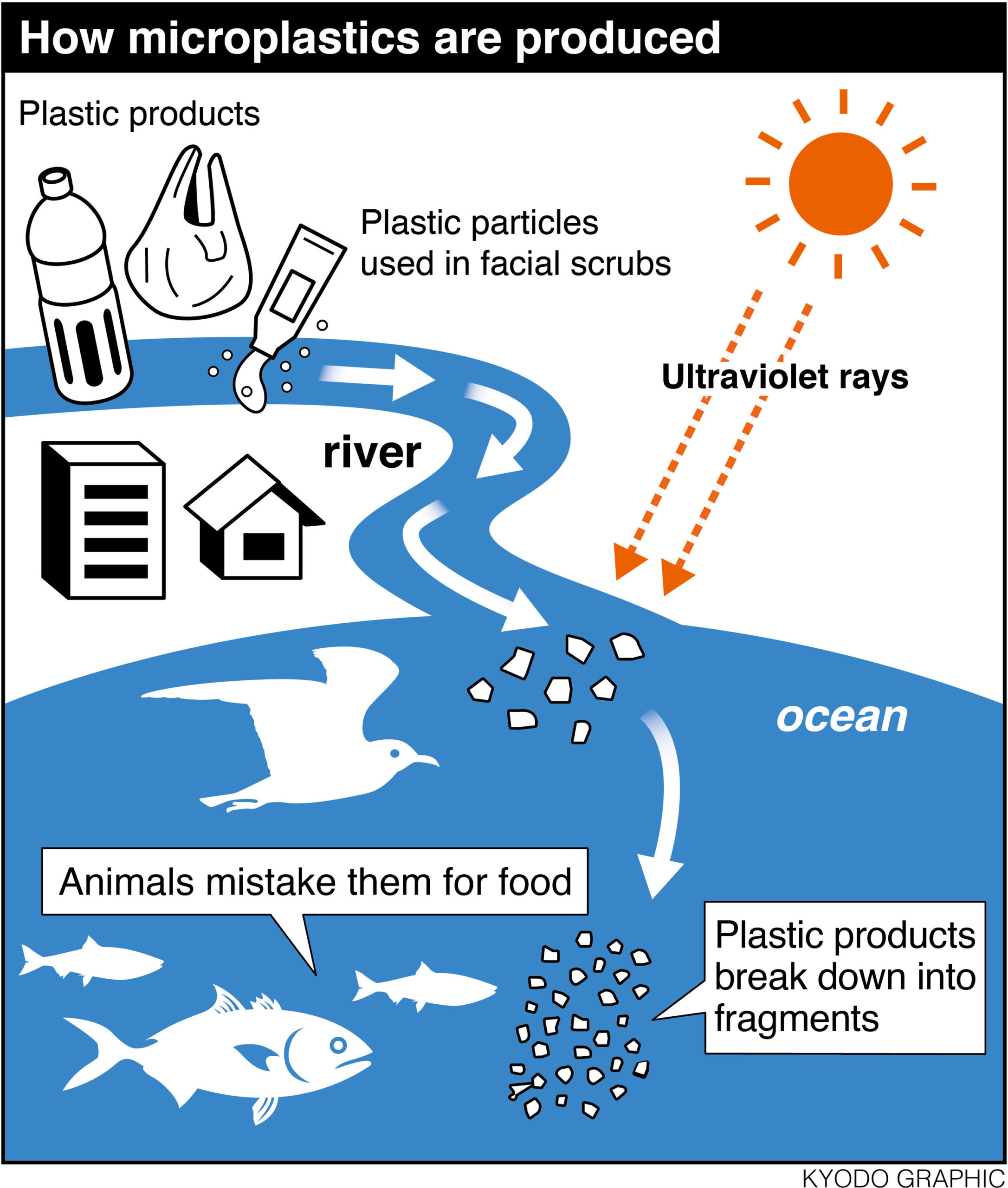

Food or Plastic? That is the question. Estimates of the World Economic Forum indicate that by 2050 there will be more plastic in the oceans than fish. Every year, 8 million tons of plastic bags end up in our waterways and disrupt our environment and put our food supply in jeopardy. We are effectively dealing with both an environmental and a public health crisis. Animals can easily mistake plastic products for food – a dead sperm whale was found with 13 pounds of plastic its stomach last November– and plastic products break down into fragments transferring hazardous chemicals and toxic heavy metals, often added to add strength, quality, and pigment to these products. Leached out metals can then end up in foods and drinking water.

Political saliency of the issue reached unprecedented levels last year — dubbed as the “Year of the Straw” — and a rising number of state and city administrations have adopted legislation to reduce use of single-use disposable shopping bags, straws and food containers. Several new bans and fees for single-use plastics have went, or are about to go, into effect in 2019.

1: New Rules

As of January 2019, in the state of New Jersey alone, nearly 20 municipalities had passed ordinances to ban or reduce sales of plastic carryout bags by stores. Some of these include additional provisions prohibiting the sale of expanded polystyrene (Styrofoam) food containers and plastic straws also. After five years of legal battles, a Styrofoam ban went into effect this January in New York City as well. Legislation restricting or disincentivizing the use of single-use plastic bags in the city and state, however, is yet to be adopted. The recently presented New York State FY 2020 Executive Budget included a proposed action to ban the single-use carryout bags at the state level. New York has now the opportunity to become the second state (after California) to pass this kind of legislation in the US.

California effectively banned single-used plastics and mandated fees on reusable carryout bags back in 2014, limited the distribution of plastic straws in restaurants, and is now gearing up for an even more ambitious stand on the matter. On February 21, 2019 California legislators introduced Assembly Bill 1080 to phase out single-use plastics by 2030. Last June 2018, New Jersey lawmakers also introduced comprehensive legislation (Measure S2776) to ban food service businesses from selling plastic carryout bags, expanded polystyrene (Styrofoam) food service products, and single-use plastic straws, which is in the final stages in the legislative process. But not all states have been keen on tightening regulations on plastics and, as with bans on sugary beverages taxes, some have passed preemptive “ban the ban” laws (e.g., Arizona and Missouri in 2015; Michigan and Wisconsin in 2016, Minnesota in 2017), preempting cities from taking steps toward anti-plastic bag legislation.

But the majority of US cities are not affected by such restrictions and some are following in the footsteps of their State with even more ambitious policies. On January 22, 2019 the city of Berkeley, CA passed legislation which introduces a 25-cent fee per disposable cup at restaurants and, by January 2020, mandates the transition to compostable dishes and utensils for all takeout meals. In Seattle, where single-use plastic bags were banned in 2011, a new ban on plastic straws and utensils will take effect on July 1, 2019 and affect all commercial establishments serving food and beverages.

Outside the US, plastic bans have recently been adopted at the international and national levels. In October 2018, the European Parliament passed a ban on single-use plastics which will go into effect in 2021. The legislation effectively prohibits the use of disposable plastic cutlery, plates, straws, and stirrer sticks. It is estimated that the cost of marine litter paid every year by the EU is between $295 million to $793 million. In Asia, South Korea and Taiwan are leading the way. As of January 2019, South Korean grocery stores and supermarkets are prohibited from giving single-use plastic bags to their customers, unless they purchase fresh fish or meat. Beginning this year, plastic straws were banned from fast food restaurants in Taiwan. The ban is part of the country’s a longer-term plan to phase out the use of plastic straws, bags, utensils, cups and containers by 2030.

Multinational companies like Starbucks, IKEA, and McDonald’s have also started making pledges to reduce single-use plastics and straws in their chain stores in the next couple of years. Some professional associations have joined the wave of anti-plastic initiatives and made public announcements about their short and long-term goals. For instance, last Spring 2018, the American Chemistry Council set the goal of having all plastic packaging being recycled, reused or recovered by 2040.

A key question to those of us interested in shifting the current, unsustainable landscape of plastics in the food system is, however: to what extent do these policies work in practice? A review of studies which evaluated the impact of plastic bag bans and fees since 2010 reveals that in San Jose, CA a ban on plastic bags combined with a 10-cent fee on paper bags cut neighborhood plastic bag litter by half and river litter by two thirds, compared to pre-ordinance levels. Evidence on plastic bag litter three years after California’s statewide ban on plastic bags also reveals the policy effectiveness with a more than 70 percent drop in plastic bag waste in 2017 compared to 2010 levels. Some experts however underscore that fees seem to be more effective than bans alone. For instance, Washington DC introduced a 5-cent thin plastic bag fee in 2010 which helped cut use of single-use carryout bags and related river litter by 60 percent. Conversely, credit given for bringing your own reusable bag (e.g., in Maryland) have shown only modest reductions in single-bag use.

2: Why it matters

A prime goal of food policy is to advance human and environmental health in tandem. While synthetic waste reduction policy is less prominent in food policy agendas and discourse, it offers a strategic opportunity to improve human and ecological well-being. Re-framing plastic waste as a food supply and safety issue forces us to acknowledge that social and ecological processes and tightly interlocked. Simply put, broken ecosystems translate into broken food chains and unhealthy individuals.

Source: japantimes.co.jp

It has been demonstrated that plastic litter breaks down into toxic chemicals some of which are cancer-causing. Microplastics ingested by fish may also contain heavy metals, often added to give plastic bags required strength, quality, and pigment. Additionally, research has revealed that fibers from plastic products are tainting our tap water and that polystyrene, and related components, may also leach in drinking water and food-related materials. The health impacts of BPA – which is the key component of polycarbonate plastics used for the production of many water bottles and takeout food containers – are still highly debated. Some studies that have found BPA to be a “very weak” estrogen and endocrine disruptor but have been challenged by others who have found a stronger impact.

Plastics are also detrimental, if not deadly, for both aquatic and terrestrial animals. Not only does it take hundreds of years for plastics to biodegrade in oceans, but marine animals often mistake plastic bags as food or are trapped by them. Even cattle can ingest plastic bags, leading to depression, reduction of milk yield, and suspended rumination.

3: What alternatives do we have?

If cities and urban dwellers are to significantly reduce their consumption of single-use plastics within the next decade or so, what are the policies that will achieve this goal? Researchers, businesses, and plastic-free lifestyle activists around the world have started coming up with promising, yet often hard-to-implement solutions. These seek to promote elements of the four-pronged “refuse, reduce, reuse, and recycle” approach at the individual, retail, and/or industry level.

At the individual level, solutions range from replacing thin-film plastic bags with textile options, swapping disposable plastic food wraps with reusable beeswax sheets (which can last for about a year), storing fruits and vegetables in cotton mesh, and using glass or metal bottles or jars for conserving food (see more tips for a plastic-free fridge). Bring-your-own practices are also becoming more ubiquitous — from bags to cups, food containers, and cutlery.

The food retail industry is also taking notice and some plastic-free grocery store experiments were launched in several cities around the world. In 2018, Amsterdam was the first city in the EU to have a grocery store with a plastic-free aisle. Other zero-waste supermarkets have opened in Hong Kong (e.g., Live Zero and Edgar), Brooklyn, Sicily, Malaysia, and South Africa. With the growing popularity of online shopping some entrepreneurs have embarked on developing zero-waste online shopping platforms like Loop – a service that will allow customers to shop in packaging that will be collected, cleaned, refilled, and reused – in parallel to innovations in brick-and-mortar retail. Loop plans to launch its services in Paris and the New York region (including NJ and PA) this Spring 2019.

Other proposed solutions come from material engineering scientists and the R&D departments of the food packaging industry. In the US, the Department of Agriculture has piloted the use of milk film as a healthy and environmentally sustainable alternative packaging that helps preserve perishable foods. A supermarket chain in the UK has also recently launched a pasta box made from 15% recycled food waste produced in the processes of making the pasta itself. More familiar alternatives come from innovations in the plastics industry itself with products such as compostable trays and bioplastics produced with bacteria.

Despite growing experimentation and the increasing number of alternative options being tested, some open questions still persist and warrant closer examination as we make our way toward a plastic-free urban foodscape. In cities heavily dependent on public transit – like New York City – customers may be less inclined to bring their own glass or metal containers when grocery shopping. Less plastics might also require an overhaul of entire segments of the food supply due to different shelf life for items packaged in materials other than plastics. Additionally, bioplastic is degradable but only when sent to industrial compost sites, that can provide the needed amount of heat, and it is not uncommon that compostable trays get stuck and break some of the organic waste processing equipment. Lastly, new materials tend to cost more, and new practices tend to require more time thus making plastic-free lives less accessible to lower income communities.

Yet, the challenge remains. In the US, packaging accounts for one quarter of landfill waste, much of which comes from food-related packaging. The country uses around 240 pounds per capita every year which, considering the health and environmental impacts of this material, points to the pressing need for innovation and policy change. Finding viable solutions is even more urgent when considering that China – the country processing about half of the world’s recyclables – stopped accepting many of them last year.

Ultimately, both market forces and public pressure will be needed to reduce the use of plastics. By developing and testing various public policies that can reduce the external costs that the plastics industry now imposes on health and the environment, governments and civil society groups can encourage further action to reduce this waste.

By Rositsa T. Ilieva and Shari Rueckl