In mid-August, several CUFPI staff members traveled to Toronto, Ontario for a meeting entitled WC2 (World Class Universities in World Class Cities). In light of our recent success in obtaining universal free school meals for the 1.1 million public school students in New York City, and because of my book, Free For All: Fixing School Food in America, Canadian Food activists in the Coalition for Healthy School Food asked me to participate in a public forum on School Lunch. Canada has no national school meals program. Instead, some students in some schools are served by a patchwork of programs, funded by private, municipal, and in some cases Provincial contributions. Some of these are heavily reliant on food donations from local food banks and industry sponsors, leading to a large role for snack foods and shelf-stable products, not an optimal path for a nation in which a third of all children are obese or overweight.

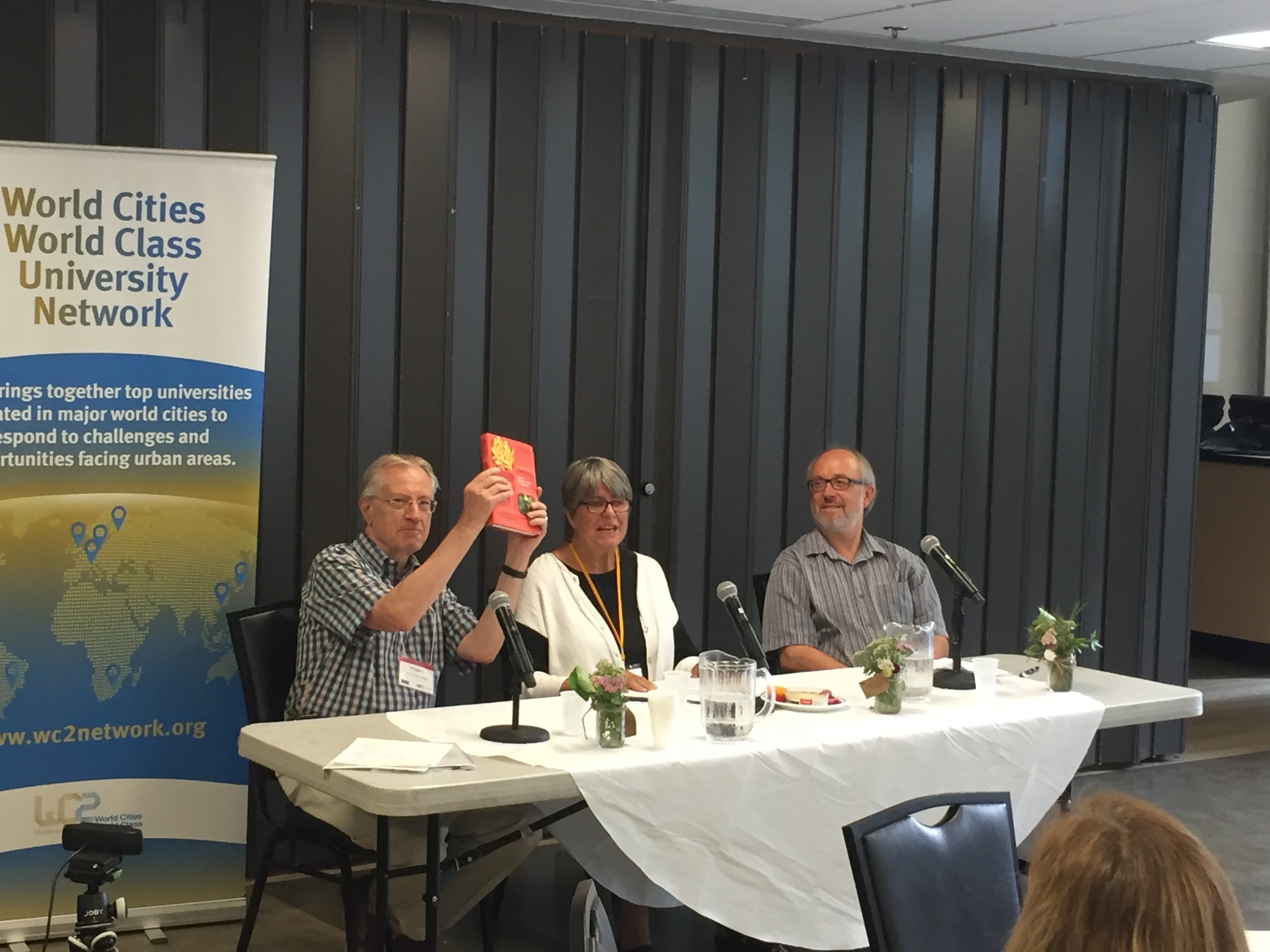

Senator Art Eggleton, former Mayor of Toronto (pictured at left above), has introduced a resolution to the Canadian Senate calling for a national nutrition program for children and youth. The early evening session, “Getting to Yes”: National Nutrition Programs for Children and Youth Strategy Meeting, began with a brief talk by Senator Eggleton in which he explained that his resolution was a measure to promote health and learning, followed by even briefer comments by me, Toronto City Councillor Joe Mihevc (pictured at right above), and representatives of the coalition and several other organizations involved in existing school food programs.1

Given an opportunity to help design a national school food program that would avoid the pitfalls that have hampered our programs here in the US, what advice can those who have been active in school food in the United States suggest?

Here is what I offered in my “Five Minutes of Free Advice.”

- FRAMING. You are absolutely right to present this as a measure for health, learning, and community building. DO NOT CALL IT HUNGER. The health implications are clear and you have summarized them. The research on learning outcomes is compelling. Eating is an intimate act, and a well-designed school food program can help to bring students together. Think summer camp.

- UNIVERSAL is the key. You must avoid the seduction of a means test and of visibly targeting this to poor youngsters. A means test is often defended as “efficient,” but in fact it is profoundly inefficient, generating vast quantities of paperwork and documentation. A means test has no place in the public schools and other youth serving programs; it poisons any program it touches. When kids reach the pre-teen years, they become acutely aware of social distinctions. If the program becomes identified as something for the poor, even poor youngsters will forego it, or eat meals steeped in shame.

- Listen to those most affected. I was glad to see that you propose a consultative process, but consultation with parents, students, teachers, principals and cafeteria workers needs to be built into not only the design phase, but the ongoing management.

- Nutrition standards. This need for ongoing consultation has implications for nutrition standards. Industry will push for one-size fits all uniformity, but Canada is a very large country with many different traditions and ecological realities. What can be locally sourced, sustainably produced, and contribute to the strength of the local economy will surely vary. Salad bars have worked well in New York City—and superbly in California, but in Alaska, not so much.

- Menu Planning. Nutrition is only one factor that affects the menu. Does a school have a lunchroom or cafeteria big enough to hold the students? If not, you need a menu that can be eaten in classrooms -— “grab and go.” Salad bars are great, but they take time. You need a lunch period long enough to accommodate them.

- Procurement. We made a huge mistake in the US by requiring acceptance of the lowest bid. We are only now beginning to be able to give weight to sustainability, fair labor practices, and the local economy in our purchases.2

- Role of students. My all-time favorite school lunch program is the one at Pacific Elementary School in Davenport, CA. The 5th graders prepare the school lunch; the 4th graders set the tables and decorate them with flowers from the school garden. Think about school meals as whole-school activities.

- School food labor. School Food jobs need to be “Good Food Jobs,” jobs that promote health and are good jobs for workers, including a living wage, comprehensive benefits, and career paths.

The brief comments by speakers were followed by an open forum in which those in attendance were urged to contact their legislators and mobilize the organizations of which they are part. Subsequent reports from Canada suggest that a national conversation about a youth nutrition program has indeed accelerated, with Coalition for Healthy School Food founder Debbie Field and supporter Professor Sara Kirk doing Canadian Broadcasting company interviews across the nation—twenty-six of them so far.

By Jan Poppendieck, CUFPI Senior Fellow

References

1 Kirk, S. and Ruetz, A. (August 28, 2018) “How to make a national school food program happen”, The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/how-to-make-a-national-school-food-program-happen-102018

2 For more on the constraints on procurement and the movement to overcome them, see J. Poppendieck, Free For All: Fixing School Food in America, (Berkeley: UC Press, 2010),pp 292-296. And explore the good Food Purchasing Program at https://goodfoodpurchasing.org/