On September 6, Carmen Fariña, the New York City School Chancellor announced that lunch at New York City public schools will be available free of charge to all 1.1 million students beginning this school year. Three quarters of New York City schoolchildren had already qualified for free or reduced-price lunches. The new initiative reaches another 200,000 children, saving their families about $300 a year per child.

The decision to offer lunch free of charge to all students is a big win for New York City students, parents, teachers, school administrators, and tax payers. Students who were not eligible for free meals but could not afford to pay for lunch are the most obvious winners. These include children from families with incomes over the threshold, and students who were income eligible but whose families did not choose to apply for fear of jeopardizing immigration status or for other reasons. Universal free school meals, however, will benefit all students. Students who have been receiving free school lunches will now be able to do so without shame or stigma. It won’t disappear overnight, but within a few years, no one will remember when it was cool to make fun of kids who were getting a free meal. Lunch at school will just be a normal part of the school day for all, a unifying rather than a divisive social encounter. The reduced paperwork burden will free up resources for food and labor, leading to even healthier, tastier food for all participants. Well-fueled students will be more ready to learn, enhancing the classroom experience for all.

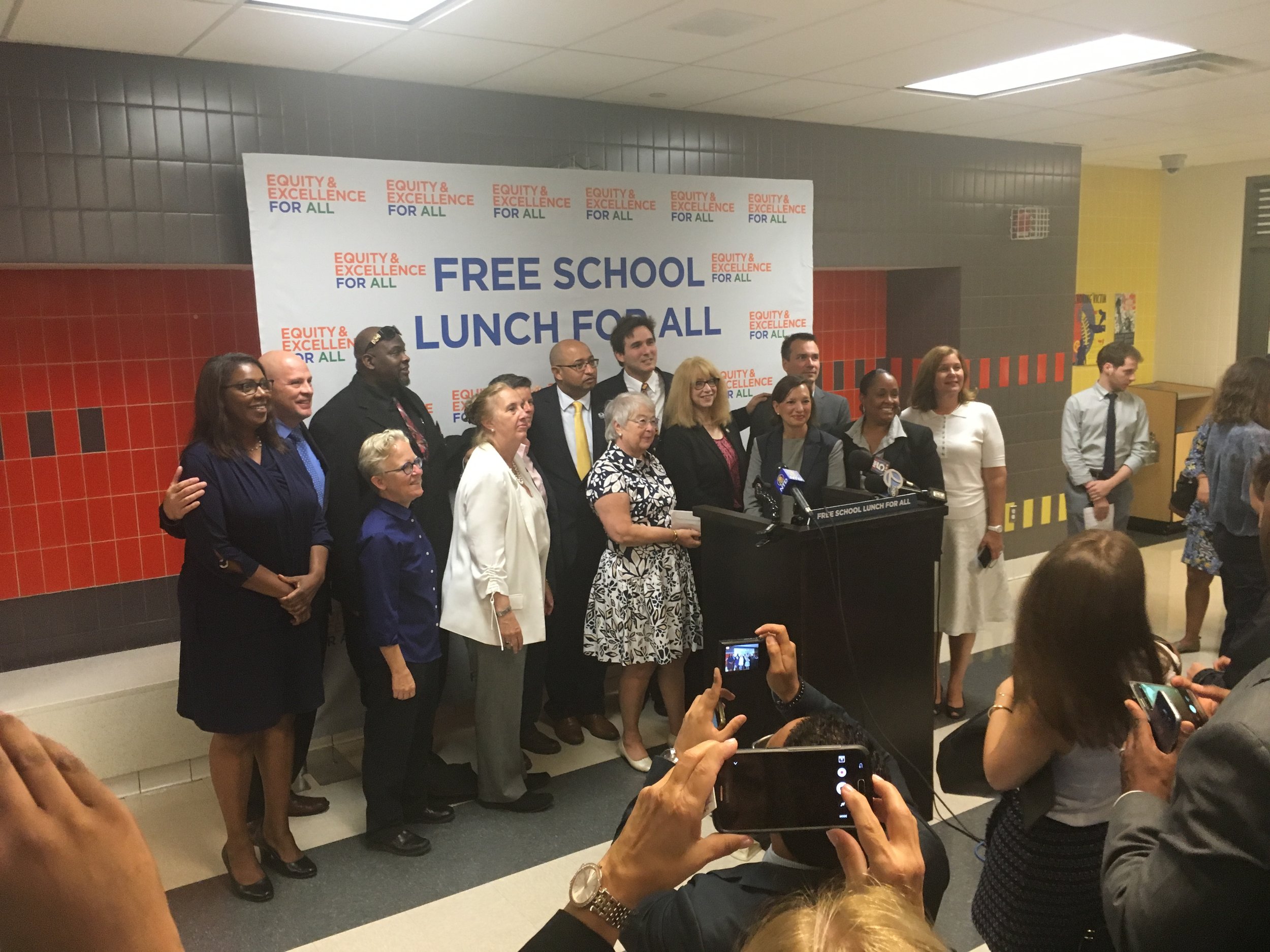

On September 6 New York City School Chancellor Fariña announced at a press conference at PS51 that lunch at New York City public schools will be available free of charge to all 1.1 million students beginning this school year.

Parents who have been purchasing meals at school can now devote the savings to other needs. Further, they can stop worrying about accumulated school lunch debt. This will be a boon to principals, teachers and parent coordinators trying to engage parents with school activities: no more parents staying away from parent-teacher visits for fear of being dunned for money owed. And principals will no longer have to perform or delegate the hated job of lunch debt collector.

Parents who have been giving their children cash to purchase food from the corner store or preparing bag lunches at home can now count on a healthy meal at mid-day; they can stop worrying that their children will spend “lunch money” on unhealthy snacks, and quit scrambling for something to put in the lunch bag.

Teachers can now integrate the lunch hour into their lesson plans, not only to teach much needed nutrition education, but also to harness the power of food to teach math, science and language arts. Since lunch will be freely available to all students, teachers can reasonably and responsibly craft assignments that make use of the lunch menu and experience.

Taxpayers will benefit. In the short run, they will be getting more for their money as schools invest cost savings in improving meals. In the long run, school food can be a powerful tool to reduce obesity and diet related disease and the resulting strain on health care budgets and resources. And the economy of the city will benefit as more jobs are added in kitchens and cafeterias.

For the time being, parents will still be asked to fill out income forms needed to allocate Title One funds, but these will have no bearing on the lunch program. In the long run, the City has the option of using census or other income survey data for this purpose. It can do away with these forms altogether when it chooses to do so.

There is another lesson in the city’s decision to provide free lunch for all New York City public school students: activism works. For several decades, parents and consumer groups have advocated for making healthier, tastier meals available to all the city’s school children. From lawsuits in the early 1980s to more recent letter-writing campaigns and community mobilization, these organizations have kept up the pressure on the city school system as well as on city and federal government to use the school meal program to reduce hunger, improve health and academic achievement and relieve parents of one more worry. In the current victory, Community Food Advocates, founded in 2010 to improve the health and well-being of low-income New Yorkers by promoting policies that strengthen and support the full utilization of publicly funded-income and food support programs, played a key role in achieving this victory. Through its Lunch for Learning Campaign, it brought together children, young people, parents, teachers, health professionals, labor unions, elected officials, researchers and others to convince New York City that it was easier to accede to their reasoned arguments than to continue to object.

Because of the campaign’s activities, the future of school meals in New York City is brighter than it has ever been. Now is the time for parents and students to get involved in making sure that school food lives up to its potential. And for activists and the food justice movement to learn once again that good ideas, moral arguments, and mobilized communities are a powerful recipe for more equitable food policies.

By Jan Poppendieck, Senior Faculty Fellow, CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute