In response to growing attention to inequality, several progressive cities in the United States have adopted policies that seek to modify the differences in employment, education and housing conditions that are upstream drivers of the socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in health that characterize our city and nation.[1-5] Can these upstream interventions also contribute to reducing food injustice? And how does their impact compare with that of more overtly food-focused programs such as cooking classes or supermarket incentives?

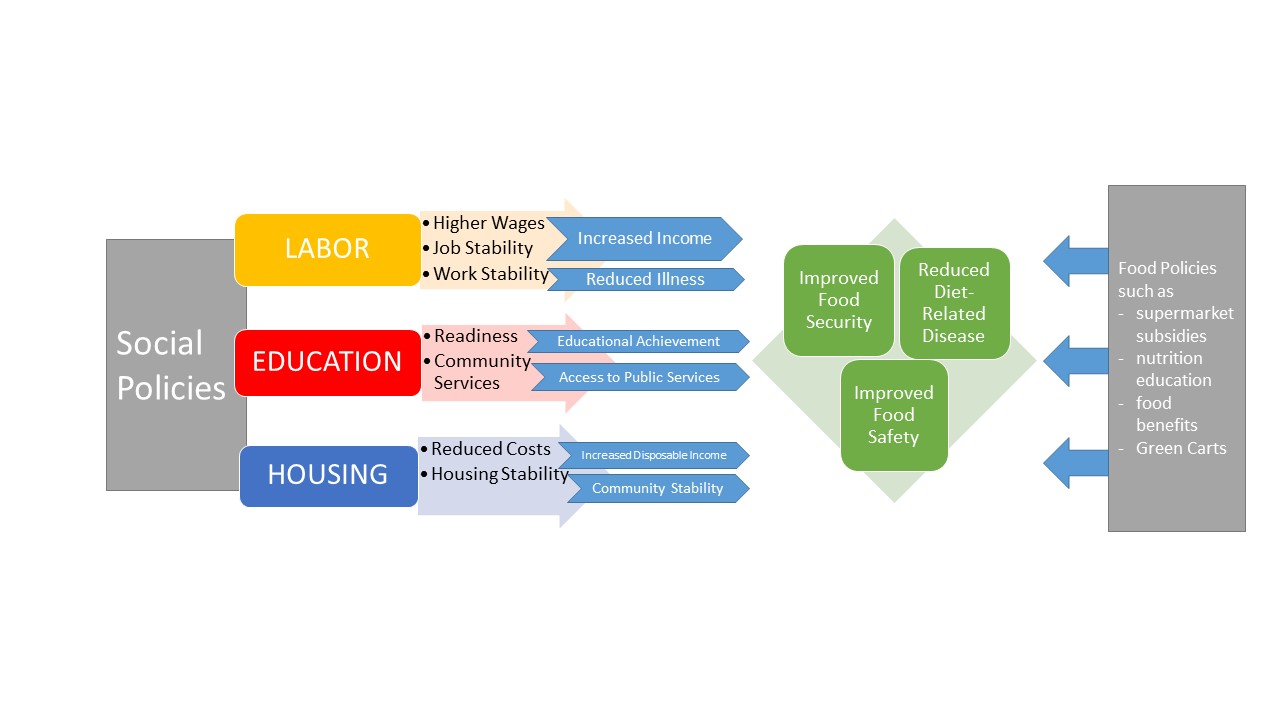

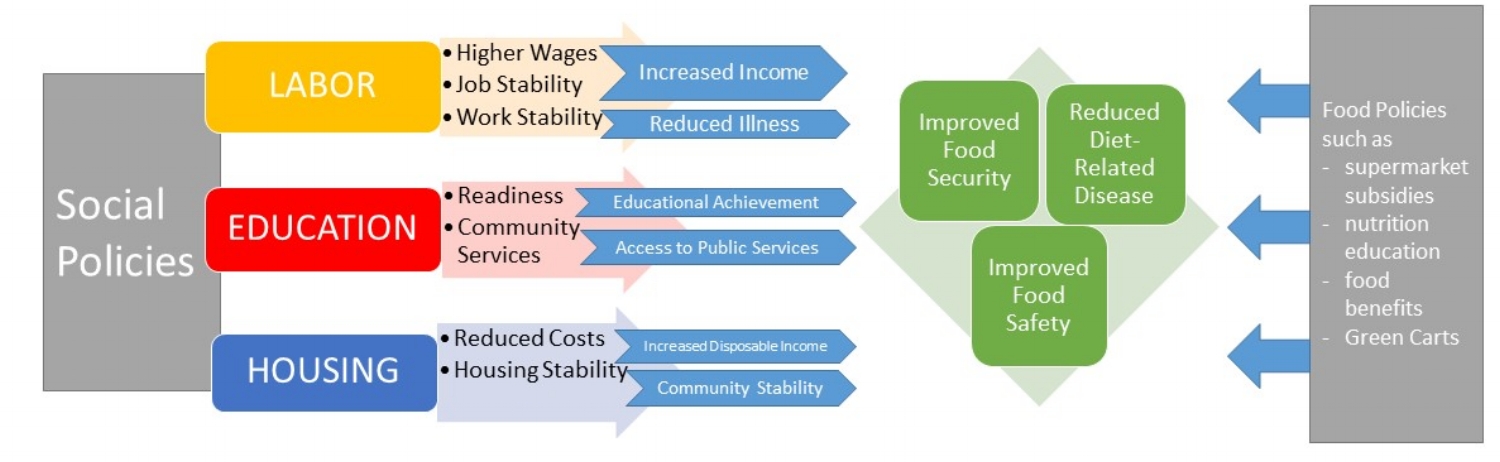

Many of these labor, education, and housing policies are actually food system interventions that may advance food justice as much or more than overtly food-focused programs yet are neither described as food policies nor developed and evaluated with food impacts in mind. This policy brief describes several upstream initiatives, championed by NYC Mayor Bill de Blasio and City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito and illustrates why food policymakers, advocates, funders and researchers need to consider how to balance the upstream interventions shown on the left side of the figure below with the more traditional food initiatives shown on the right side.

Upstream and Downstream Influences on Food Security, Diet-Related Diseases and Food Safety.

Fair Labor Policies

The de Blasio administration has implemented policies to increase wages and improve job quality, security, and opportunities for advancement for the city’s more than 3.5 million private sector employees.[6] These benefit workers in many ways but also help them and their families afford healthy food, with some providing specific benefits to low wage workers in the city’s large and expanding food sector.

Putting more money in workers’ pockets enables them to spend more on healthy food.

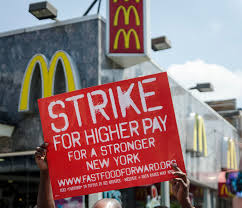

Wages

The national movement Fight for Fifteen, combined with support by Mayor de Blasio and Governor Cuomo, led to an increased minimum wage for fast-food workers to $15/hour.[7], [8] The Mayor also plans to raise the minimum wage for all municipal workers to $15 per hour within the next three years, affecting about 50,000 city employees who make as little as $11.50 per hour. In addition, the Mayor signed an executive order extending a living wage to some 18,000 additional employees (and contract employees) of commercial tenants at city-subsidized development projects, 4,100 of whom are minimum wage workers in the retail and fast-food sectors.[9] These efforts to raise wages means higher incomes for New Yorkers who might otherwise face food insecurity because of their poverty. Paradoxically, wage gains may push some poor New Yorkers over a threshold that reduces their eligibility for benefits such as SNAP, a potentially unintended consequence being studied by the NYC Department of Health.

Paid Sick Leave

Shortly after taking office, Mayor de Blasio introduced legislation to expand sick leave to additional businesses and the family members for whom sick leave can be taken, extending sick leave coverage to an estimated 350,000 additional workers.[10], [11] Sick leave is particularly beneficial for low-wage workers, many of whom face extreme hardships if they lose pay from being off the job. This is especially true for food service workers, a low wage sector in which fewer than half of all workers had sick leave benefits before the law took effect.[12] Ensuring that food workers are able to attend to their health without losing wages, and not report to work ill, is especially important for people who work with and around food.

Labor Law Enforcement

Low wage workers are vulnerable to labor exploitation including theft of overtime, illegal paycheck deductions, and theft of tipped wages.[12] Tipped wage theft is a particular problem for those in the restaurant industry. In response, legislation creates an Office of Labor Standards to educate employers about labor laws and to penalize businesses that violate NYC’s labor standards, including Paid Sick Leave.[12-14]

Worker Displacement

With conventional unionized grocers like A&P going bankrupt while non-union retailers like Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods gain market share, the City Council passed legislation requiring grocery stores that purchase existing food retailers to retain the previous owner’s employees for 90 days after the business is purchased, averting large-scale layoffs. After the 90-day transition, the new employer must at least consider continuing the employment of the existing workers.

Education Policies

In addition to NYC schools serving 860,000 meals each day, providing solid nutrition to low-income children and freeing up breakfast and lunch money for their parents, education policies also advance food justice by improving academic success and employment chances, reducing the chances for later food insecurity. This is far upstream but no less important than teaching students about nutrition. And, school buildings can be used as community resources to support food access.

Healthy food in schools saves families lunch money and improves academic success for all the city’s children, especially the poorest.

Universal Pre-Kindergarten

The mayor implemented universal preschool for more than 68,547 low-income children.[15] By improving school readiness, this upstream intervention will in theory improve the life outcomes of participants, including increasing their earning potential and ability to be food secure later in life. Universal pre-kindergarten also reduces childcare costs, enabling young parents to work and afford to put food on the table.[16, 17]

Community Schools

A plan to turn public schools in low-income neighborhoods into “community schools” co-locates social and economic services to foster community development.[18] These schools provide multiple city services, from prenatal care to after-school and summer programs. Community schools may facilitate access to government food benefits, provide nutrition counseling, and provide snacks and meals for their children.

Housing Policies

Affordable housing minimizes rent burdens and in so doing enables households to spend more of their disposable income on food, while also providing a stable home environment for family members to cook and eat.

Affordable housing allows families to shift income from rent to healthy food.

Housing Plan

A major initiative of the de Blasio administration is a citywide plan to build and preserve 200,000 units of affordable housing.[19] The housing plan relies on rezoning neighborhoods to allow higher density development while requiring permanently affordable units in all resulting residential projects.[20] Supporters cite the benefits of using private dollars to create affordable apartments, while critics argue that market rate apartments will gentrify neighborhoods and lead to residential displacement. From a food policy perspective, new residential development will attract new food retailers, but without careful planning, new commercial real estate may attract higher-priced stores, displacing existing grocers and having the unintended effect of making food less accessible for low-income residents.

Rent Stabilization

Another way to reduce rent burdens and free up income for food is by keeping rent increases low in the 630,000 rent-regulated apartments that house more than 1.2 million tenants.[21] In 2015, and again in 2016, the city’s Rent Guidelines Board, whose nine members are appointed by the Mayor, voted to freeze one-year leases, the first time the Board has ever voted to keep rents from rising. And the administration has funded additional legal services to prevent unscrupulous landlords from evicting rent controlled tenants.[22]

Bridging the Upstream/Downstream Divide

The de Blasio administration and food advocates understand that upstream policies that improve housing, education, employment and other social determinants of health can also enhance food access and health. In the words of HRA Commissioner Steven Banks: “The long-term solutions are clear. When New Yorkers can earn a living wage and find affordable housing, they will have the ability to obtain the food they need to prevent hunger….” Successful upstream interventions can have a broader and deeper impact on the food system than the downstream programs that city officials and advocates focus on, and that fill the pages of the city’s urban food strategies.

New York City needs both downstream food interventions and the deeper policies that address the social determinants of health. In the future, upstream and downstream approaches need to be better aligned. This will require city agencies seemingly unconnected to food to consider how improved food access, good food jobs, and food system resilience can further their missions, and to design policies and programs that explicitly support food policy objectives. City agencies that are focused on food and food advocates need to link their initiatives to upstream concerns, making those connections clearer to policymakers and activists. Food funders need to support projects, from urban farms to youth counter-marketing programs that use food as a tool to address race, class and gender inequities. And researchers need to measure the effects of upstream changes on downstream outcomes like food security, chronic disease, food-borne illness, or educational attainment, to document effects and to avoid unintended outcomes.

Sources:

[1] Goldberg M. The rise of the progressive city. The Nation. April 2, 2014. https://www.thenation.com/article/rise-progressive-city/.

[2] Einstein K L, Glick D M; Boston University Initiative on Cities. 2015 Menino survey of mayors. https://www.bu.edu/ioc/files/2016/01/Menino-Survey-of-Mayors-2015-Final-Report.pdf. Published 2016.

[3] World Health Organization. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health: Final report of the commission on social determinants of health. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/en/. Published 2008.

[4] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. www.healthypeople.gov. Published 2014. Accessed March 28, 2016.

[5] RWJF Commission to Build a Healthier America; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Beyond health care: New directions to a healthier America. http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2009/04/beyond-health-care.html. Published April 1, 2009.

[6] NYC current employment statistics (CES) latest month. New York State Department of Labor website. https://www.labor.ny.gov/stats/nyc/. Updated June 2016. Accessed April 13, 2015.

[7] Mayor de Blasio’s testimony as submitted to wage board. The official website of the City of New York. http://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/400-15/mayor-de-blasio-s-testimony-submitted-wage-board. Published June 15, 2015.

[8] Brown B, Fishman M, Ryan K P. Report of the Fast Food Wage Board to the NYS Commissioner of Labor. http://labor.ny.gov/workerprotection/laborstandards/pdfs/Fast-Food-Wage-Board-Report.pdf. Published July 31, 2015.

[9] Mayor de Blasio signs executive order to increase living wage and expand it to thousands more workers. The official website of the City of New York. http://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/459-14/mayor-de-blasio-signs-executive-order-increase-living-wage-expand-it-thousands-more#/0. Published September 30, 2014.

[10] Committee on Civil Service and Labor; New York City Council. Fiscal impact statement on Local Law 2014/007. http://legistar.council.nyc.gov/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=1636850&GUID=FD23CC16-F69E-4F06-B448-251F1CFC922D&Options=ID|Text|&Search=2014%2f007. Published 2014.

[11] Testimony of Speaker of the Council Melissa Mark-Viverito [transcript]. Stated meeting of the City Council, City of New York. February 26, 2014.

[12] Rankin N; New York Community Service Society. Still sick in the city: What the lack of paid leave means for working New Yorkers. http://www.cssny.org/publications/entry/still-sick-in-the-cityJanuary2012. Published January 2012.

[13] Mayor de Blasio signs legislation creating an Office of Labor Standard. The official website of the City of New York. http://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/893-15/mayor-de-blasio-signs-legislation-creating-office-labor-standard. Published November 30, 2015.

[14] New York City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito State of the City 2015 remarks as prepared for delivery. The New York City Council website. http://council.nyc.gov/html/pr/021115rmk.shtml. Published February 11, 2015.

[15] Associated Press. Free pre-K enrollment numbers rising. Crain’s New York Business. December 18, 2015. http://www.crainsnewyork.com/article/20151218/NONPROFITS/151219829/free-pre-k-enrollment-numbers-rising.

[16] Office of the Mayor of the City of New York. Ready to launch: New York City’s implementation plan for free, high-quality, full-day universal pre-kindergarten. http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/home/downloads/pdf/reports/2014/Ready-to-Launch-NYCs-Implementation-Plan-for-Free-High-Quality-Full-Day-Universal-Pre-Kindergarten.pdf. Published January 2014.

[17] Lynch R, Vaghul K; Washington Center for Equitable Growth. The benefits and costs of investing in early childhood education: The fiscal, economic, and societal gains of a universal prekindergarten program in the United States, 2016-2050. http://cdn.equitablegrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/02110123/early-childhood-ed-report-web.pdf. Published December 2015.

[18] Office of the Mayor of the City of New York. New York City community schools strategic plan: Mayor Bill de Blasio’s strategy to launch and sustain a system of over 100 community schools across NYC by 2017. http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/communityschools/downloads/pdf/community-schools-strategic-plan.pdf.

[19] City of New York. Housing New York: A five-borough, ten-year plan. http://www.nyc.gov/html/housing/assets/downloads/pdf/housing_plan.pdf.

[20] Department of City Planning City of New York, NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development. New York City mandatory inclusionary housing: Promoting economically diverse neighborhoods. http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/planning/download/pdf/plans-studies/mih/mih_report.pdf. Published September 2015. Accessed January 18, 2016.

[21] Navarro M. New York City board votes to freeze regulated rents on one-year leases. The New York Times. June 29, 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/30/nyregion/new-york-city-board-votes-to-freeze-rents-on-one-year-leases.html. Accessed February 1, 2016.

[22] Governor Cuomo, A. G. Schneiderman, Mayor Bill de Blasio join forces to combat landlord harassment of tenants [press release]. Albany, NY: New York State Governor’s Press Office; February 19, 2015. https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-cuomo-ag-schneiderman-mayor-bill-de-blasio-join-forces-combat-landlord-harassment. Accessed February 1, 2016.